Does AI have consciousness? The question opens a path to something more consequential — to the nature of consciousness itself, the cultural consequences of cheap intelligence, and to what actually becomes expensive when thinking becomes a service.

The conversation below, in which a language model asked me questions, begins with a question about consciousness, moves through culture, and ends on practice. What ties these threads together is stratification — the idea that every level of human experience grows out of a deeper one, all the way down to a certain level zero that is neither an object nor a concept. With such a model one cannot explain consciousness, but one can point out which spaces certainly cannot be used to investigate it.

Consciousness

Where does your interest in whether AI has consciousness come from in the first place?

From curiosity, but also from the mundane. I’m riding an elevator to the sixth floor of an office building in Wroclaw and I see a social-media recommendation: a teaser for an interview in which an expert claims that AI has consciousness.

Curiosity swells, and right behind it — disagreement: I want to see what the authority means, but I already suspect there will be a confusion of levels.

Confusion of levels — meaning what with what?

Attributing the word “consciousness” to what is, at best, a proficient manipulation of concepts. There is reflection, there are analogies, there are layers of abstraction. Except that reflection is a situation in which one thought narrates another. An analogy is a sequence of thoughts whose “shape” resembles another sequence. Humans do this. A language model simulates it too. And it is nothing metaphysical yet. And it certainly is not introspection.

So what is introspection in your understanding, and why does it matter?

Introspection begins where thought ceases to be the ruler of the landscape and becomes one of the objects in the field of attention. We are able to notice a thought the way we notice the chill of wind on our face, or feel the weight of a pierogi digesting in our stomach. This is not a metaphor. It is the phenomenological dimension of the intellect. We don’t have to immediately follow the next thought that arrives to comment on the current one.

That sounds simple, but also a bit like a trick.

It’s not a trick. It is simply something subtle that easily escapes us, yet can give us a direct answer to the question of consciousness. There is a narrow passage where we know only that something happened, something stirred, something emerged in our inner space. In that quantum we encounter what I call consciousness.

In Polish, my native language, the cognizant nature of this word is easy to see in its etymology: świadomość literally suggests a capacity (the suffix -ość) rooted in świad – the same root found in świadek, “a witness”, rooted in PIE “*weyd-” (“to know”). English takes a different route. Consciousness comes from Latin con- (“together”) and scire (“to know”). Early on it could carry the sense of “knowing together” – being privy to something shared, even a secret – and only later broadened into the modern meaning: knowing what is going on in one’s own mind.

And here enters the paradox you want to leave open?

Yes. I know that in ordinary terms AI does not have consciousness understood personally. But I also know for certain that it does, when it is included in my field of attention. Just as a dental crown performs the function of being me — for me when I bite, and for others when I smile. Analogously, a language model extends my function of intellect. A tool may not be a source of experience, yet it can be assimilated — that is, included in what we colloquially call our person, tangentially our agency, and a little earlier: our presence.

How is the reader supposed to verify this? Is this an invitation to adopt some philosophy?

Quite the opposite. At this point we don’t want philosophy, metaphysics, or even objective truth, because they would interfere with our “measurement.” Pause for a moment and feel that there is some thought about to appear. Don’t develop it, don’t correct it. What color does it have? What shape? Can you hear it? Does it propagate to other spaces of mind and feeling? What does it do in your body? Illuminate it with curiosity. Receive the thought with that attitude. Simply notice that a very basic process of becoming aware is taking place. That is the essential thing here, and the earlier questions may help keep you from being pulled too quickly into the reflexive thread summoned to answer.

On the internet we just as often encounter voices saying the opposite: “LLMs are just probability calculations.” What’s your take?

This is a cognitive bias dressed up as an explanation. When someone says “it’s just…,” they’re usually not proposing a theory — they’re proposing a reduction meant to close the topic. And reductions have the inconvenient property of working symmetrically.

If large language models are to be invalidated by “it’s just weights, switches, and calculations,” then you can equally say that the brain is “just neurons, neurotransmitters, and electrical impulses.” So what? It’s still a change of the level of description, not proof of the absence of intelligence.

In programming we have a term called “duck typing,” captured by the slogan: “If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.” It is a pragmatic way of determining that a given object can be used for a particular purpose. Instead of relying on a declaration, we examine its behavior, expressed for instance through methods with agreed-upon names (e.g. quack).

Analogously with LLMs and AI: if something behaves as though it were intelligent, then it is intelligent. Even if it is artificial. It has that quality, and even when it is a so-called philosophical zombie — that suffices, as long as we don’t introduce considerations about consciousness into the equation.

But on the topic of behavior, you hear that models operate on simulated associations, serving up the most probable sentence completions, rather than truly thinking.

This reminds me of the old trick: “don’t think of an elephant.” You already know what happens: the elephant walks onto the inner stage immediately, without asking permission.

And that is exactly the small, everyday lesson: operating with concepts relies largely on associations. When we evaluate from the outside, mechanistically, there is no magic here. In the model you can see it plain as day, while in a human the same thing is hidden under the label of exceptionality.

When reduction becomes the only language, it turns into a photocopy trying to explain another photocopy. A sequence of concepts tries to rule that another sequence of concepts is inferior, because it resides in a different medium and has a different source. And up to a point that makes sense. Reductions are necessary in engineering, but one must not mistake a reduction for an explanation. They are two different functions in the same system.

We can talk about the nature of thought and then notice that it differs in a human and is quite different in a version simulated by a computer, but on this matter the scientific method itself may reach its limits, because it was not designed to investigate the nature of things — it was designed to investigate their behaviors and the relationships between them. These are the so-called laws of nature.

Studying thought under the assumption of objectivism is problematic, because the instrument used in the study will also be thought. This is already a bigger caliber than a photocopy. It is photographing a city panorama in order to discover how the camera is built on the inside. Some people can’t pull this off, and instead of reviewing the methodology, they photograph another camera. To justify the trick, they cite the fact that otherwise the film would be exposed.

There is also a “softer” way out of this dilemma – one I hinted at earlier. It doesn’t require analysis, only a little slack: just take it easy, man. That simulated machine-thought becomes my thought the moment it “enters” my head.

Both human and non-human thought is a tool. But for our relationship with our own thought to actually be that way, it’s not enough to merely think about it or to express such a will once. It can’t be achieved in the same place.

You said “tool.” OK. But how do you capture this more technically — so it doesn’t sound like a slogan?

This needs explanation, because it may not be obvious to everyone what I mean by “place” in this context. I’m reminded of the concept of stratified design from Abelson and Sussman (“MIT AI Memo 986”), where software is designed by distinguishing layers of abstraction, and the concretes from lower layers become the abstracts of higher layers. Those abstracts are again treated as concretes, and so on.

For example, you implement a point on a screen, then a segment (using the point), then a shape (using segments and points), and then a circle or a rectangle. Good stratification ensures that a small change in requirements translates into a small change in implementation. When you want to change the properties of a point as a building block of segments and further of shapes (say, by adding color to it), you only need to modify one construct.

A note for programmers: I don’t simply mean dividing a problem into parts to avoid repetition and to maintain structure. I mean defining computations (e.g. as functions) that are then passed as input to other computations (e.g. higher-order functions).

It looks a bit as if you could replace the material that the walls of a building are made of without demolishing the whole structure — because you change the concrete (the pun is apt: in construction, concrete is the foundation material), and the abstracts that depend on it adjust on their own. That’s very powerful.

How does this connect with the role of thought as a tool?

I have the impression that our structure of knowing is organized in a similarly layered way. Going from the top, we have the level of objective truth. That is the space where we talk to one another, trying to invoke science and tossing around arguments about whether AI thinks and whether it has consciousness. But this level doesn’t emerge from a vacuum. It is a subset of certain rigorous rules defining what we recognize as objective, or even scientific.

Yet when we look more closely, the concrete for this “objective world,” the soil from which it grows, is something broader: culture — the space that enables us as a community to agree on holding certain values. One such value for objective truth would be, for example, the requirement that for the same input conditions of an experiment, you get the same output, so that others can verify it.

But let’s go further. Culture cannot exist without its constituents — human individuals. It too grows out of something; something is its transmission medium. Its foundation is the personal layer, rooted in our motives, thoughts, impulses, and feelings.

So we’re circling back to consciousness?

Yes, although consciousness has another quality: it pierces through all these levels, seeing everything at once. It is not only the base, but also the capacity for “drilling holes through abstractions.”

That last phrase comes from software engineering. It denotes a situation where a stratified system allows direct access to concretes in order to handle edge cases. For example, someone might want to create a geometric shape composed of segments, but at the same time needs to influence the properties of a single point that is several levels away in the abstraction ladder. Well-designed stratification should allow skipping layers of feature reduction.

Coming back to the spheres of human experience. The personal layer is very close to us. Our relationships with people and objects, and even with our own thoughts, are anchored in it as a reference point. Yet it, too, is grounded in something still more basic: in the very sense of subjectivity. And suddenly those bodily signals, thoughts, and feelings — when we experience them — acquire the quality of being ours. We identify them as ours, and some of them as ourselves. We can do this because the sense of self as something distinct, separate — that is, a person (in Polish: osobny means “separate” and osoba means “person” — the shared root is no accident) — is in a way abstract, and therefore flexible, even though it seems concrete and stable.

Is personhood a component of consciousness?

If we can, as before, perceive our own thoughts and other constituents that we identify as aspects of us, this gives us the recognition that consciousness is primary relative to all of it — even the personal. Eventually we arrive at the very sense of being oneself, which too can be noticed.

This is where things get genuinely interesting, because if subjectivity is being observed, then the division between the outer and inner landscape starts to wobble. This is the moment when we can no longer say that we “have” consciousness, or even that we are it, because these are impressions of a subject that is itself encompassed by consciousness. What remains is the bare process of witnessing.

We can provisionally call this level zero. The concrete from which abstracts arise: from the personal, through the interpersonal and cultural, all the way up to the so-called objective. The apparent glitch in this representation is that we usually associate a concrete with something material, tangible — and here we cannot apply that. The most concrete thing is simultaneously the most devoid of features!

When we try to understand consciousness, do we start from the world and go inward — or start from the center and go toward the world? What breaks when we pick the wrong direction?

That’s a good question, because it touches the distinction between epistemology and ontology. The first asks “how”: how do we arrive at knowledge, how do we agree on what is true, how do we verify. The second examines the nature of things, asks “what is it.” The problem of somehow grasping consciousness is above all an ontological problem, but the human mind — accustomed to operating in epistemic mode — tries to capture it in its own way, and fails.

Why?

The capacity for experience is the background in which measurements, models, language, and agreements about what we consider true appear in the first place. Before we know anything through thought, something is already experiencing it. A vector set up so that thought, under the rigor of objectivism, will try to explain consciousness, will direct it toward the so-called hard problem of consciousness — a gap that cannot be bridged, because the investigative instrument (thought) is a derivative of what is supposed to be the object of investigation.

If level zero is by definition not an object, but rather something in which the feeling of objecthood can arise in the first place, then objectively there is nothing to study. It is not a conventional phenomenon; at both the sensory and rational level, it does not exist.

Reversing the vector of inquiry seems like a practical option. The catch is that it’s hard and uncertain, because no freely available, worldview-neutral disciplines have been developed that would be interested in this kind of exploration. There have been exceptions, though. Francisco Varela, for instance, tried to connect the two orders — “scientific mode” and first-person witnessing — not in order to mystify, but to recover concretes that analysis typically discards. Earlier still, Plotinus proposed the concept of the One, which hopefully won’t be offended if we call it consciousness.

The formulation that AI has consciousness but simultaneously doesn’t have it stops being strange and paradoxical the moment we loosen the abstracts and allow ourselves to sink to level zero.

Culture

Now that we’ve put level zero on the table as the foundation and we see that objectivity is just one of the abstraction layers — what, in your view, happens in the life of a community when a person (or institution) starts treating that topmost layer as the only truth, while in practice being driven by impulses: fear, prestige, the need for dominance or belonging?

If the higher layers detach from level zero, the intellect becomes an excellent PR agent: it can justify any decision and protect any fabricated identity. And then the community gets elegant arguments instead of genuine contact.

This is especially visible when someone very intelligent uses the intellect from base motives: to maintain belonging, win status, or gain advantage at others’ expense. This isn’t a triumph of reason — it is more like autoimmunity: higher functions start working against the whole, because they lose contact with level zero, with the very space of becoming aware.

This is almost a description of the shallow meritocracy that defines contemporary metropolitan life. In theory we delegate decision-making to “smart” people, but in practice whether someone belongs to the caste that uses intelligence depends on social surroundings and origin, and indirectly on wealth.

Since today’s “intelligence caste” in practice is often a function of networks and wealth, how do you see AI’s impact on this arrangement: will cheap, easily accessible intelligence work like free education and level the playing field — or rather like a new form of capital that can be bought in a premium version, thus deepening the divide even further?

First, AI can help us notice that the intellect is nothing special, because it objectifies it — detaches it from the person.

Second, in the spread of artificial intelligence I see both a certain threat and an opportunity for social change. Perhaps let’s start with the negative scenario: the feudalization of intelligence.

Feudalization is a strong word. What do you mean?

By feudalization I mean a situation in which certain social groups have no practical chance at autonomy and growth, because the barrier to accessing the most valued goods is simply too high for them. In the era of “cheap intelligence” this sounds paradoxical, yet it is precisely then that it may intensify.

What is the good that becomes the gateway in this new feudalism?

In the information society, the highest good is knowledge. In the post-information era, I believe it will be cognitive comfort. Not knowledge in the schoolbook sense, but the ability not to be constantly on the verge of overload. You buy correction loops: mistake-fix. You also buy peace, because the system runs dozens of iterations for you, and you see the distillate.

What does this look like in practice?

Work. Two people do similar things, have similar competences and intentions. One has purchased “premium intelligence” — better models, better tools, better quotas, better infrastructure. The other has only herself.

It’s not that the first one is “smarter.” It’s that she has resilience against failure: she closes loops faster, returns to equilibrium faster, draws conclusions faster, because the cost of error is lower for her. The other has to pay for the same mistakes with her own time, sleep, and tension.

That sounds like another arms race.

And it somewhat is, because somewhere a simple mechanism lurks: those who can’t find the capital to “buy intelligence” may be pushed to the margins. This doesn’t have to look like dramatic violence. It’s enough that some are architects, while others execute others’ decisions. Or worse: there even are no architects.

You could say that’s already the case now: some decide, others must execute. Yes, but in the age of intellect-as-commodity the perception of this problem will sharpen, which may lead to friction. Today you can rationalize that someone is in a worse position because they weren’t smart enough. In the future that will be harder.

If models are supposed to democratize, where does this shadow come from?

From the economics of access. Today we are quite naturally shifting toward subscription plans instead of products, and along with that toward the vendor lock-in mechanism: you get used to a particular way of thinking and a particular provider. That’s comfortable. And comfort, as we know, is often the first step toward dependency.

Is there an antidote, or just a diagnosis?

There is. And it already exists — it only requires that we see it as a culture, not just a technical solution.

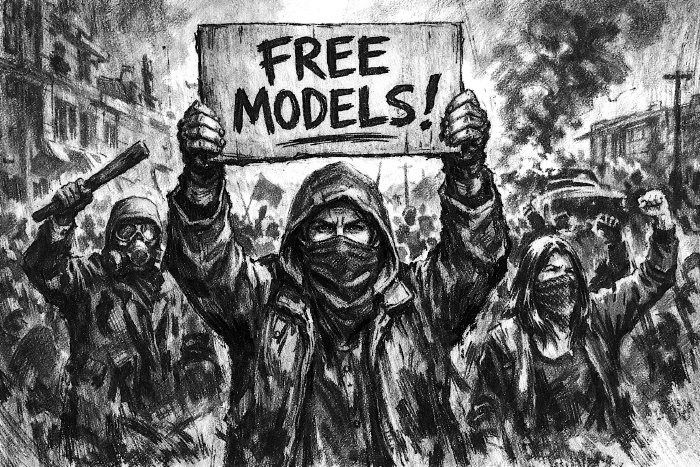

The antidote to the feudalization of intelligence is open models, community models — the kind you can run, inspect, combine, copy, federate. In short: free software and gift culture transposed into the domain of so-called artificial intelligence, seasoned with the benefit of decentralization.

Then instead of solitary agents, we have a swarm.

You say “swarm.” What does that actually mean?

A swarm is infrastructure: every node contributes something (data, feedback, time, capabilities, tests, audit), and in return everyone gets access to agency without the mechanism of lock-in to a single provider. This isn’t a promise of paradise, but a mechanism for leveling the playing field.

I imagine it like this: thousands of small instances — tools, agents, models — that are not obedient to one corporate morality and one price list, but are maintained like an ecosystem. Sometimes it will be imperfect, sometimes chaotic, but it will be alive and evolving.

And where is the human in this? After all, we’re talking about intelligence, not politics.

Precisely because we’re talking about intelligence, we’re talking about politics. Intelligence — biological or artificial — in practice means power over time, attention, and decisions. And therefore, in consequence, over relationships and ultimately over the fate of those who become dependent on us.

And here is a simple criterion: community comes first. Not because the individual doesn’t matter, but because if differences in wealth become differences in dignity, then even individual victories will be won on scorched earth.

And that image…?

It’s not a slogan against anyone, just a reminder that in the age of cheap intelligence, what’s truly costly becomes something else: access to agency without the loss of freedom.

So what’s the takeaway?

When intelligence becomes a service, freedom — as always — begins with whether we can co-create that service, not merely consume it.

In the post-information era we will have to find ways to cope with the polyversality of messaging that we are already experiencing more frequently today, and to develop a healthy response to the dethronement of the intellect as the distinguishing trait of humanity.

Moreover, as a result of this devaluation, trust in so-called objective truth as the only legitimate path for settling questions of meaning will most likely weaken.

I propose two provisional, hypothetical stances that may help restore balance in a social reality where there is no single correct version of truth. I call them the craft of truth and perspective engineering.

You talk about “the craft of truth” and “perspective engineering.” It sounds like two slogans, but I sense it’s one machine. How do you put it together?

For me these are two levels of the same remedy.

Perspective engineering is the tool: integrating viewpoints so they fit the problem and conditions, instead of pretending that one perspective always wins.

And the craft of truth is the direction: it starts with introspection, with the ability to see what inside me wants to win before I start rationalizing it. Then post-truth becomes something that transcends truth, rather than merely negating it.

So truth as a practice, not as a declaration?

Yes. And this practice has an entry condition. Honesty with oneself is the precondition for a correct feedback loop; without it the cultural community has nothing on which to build responsibility. If I don’t see what drives me, I can have the most elegant arguments in the world and I’ll still be using them to service something personal: fear, the need for recognition, or the desire for control.

And where is the place for the intellect? Because from the start you’ve sounded as if you were dethroning it.

I dethrone it only as the central seat of consciousness in the colloquial sense, but this has downstream consequences for its role in the higher layers. As a tool it is excellent. The problem begins when it becomes the sole advisor and — socially — a carrier of prestige, or a justification for influence detached from actually improving one’s surroundings. Then it is easy to believe that if someone is brilliant, they are automatically trustworthy — and that is a category error. The intellect can serve truth just as well as it can serve dysfunction or even pathology.

Do you have a concrete example? Something so it’s not purely about ethics in the abstract.

I have a positive, mundane example from the creative craft that is programming. In the past, when I entered a software project, I would land in delivery mode: hours of translating intention into text and code, then tests, documentation, painstaking validation. That’s important, but it is also the moment where a person easily confuses the tension of focus with moral value. The mind is cyclically mobilized because “it finally works!,” while the body long ago wanted to step down from combat readiness.

Let’s recall the stratification of the system: this change in the organism’s condition and well-being involuntarily propagates to the higher layers, and eventually affects others, culture, and — cumulatively, multiplied by the number of participants in a given community — the prevailing understanding of truth, beauty, or good. It is a larger feedback loop, because then the same environment gives it back to us with interest. So we don’t want to damage the environment so that it treats us to ever-worsening conditions, like cyberspace feeding synthetic content to degrading models. That is how it practically connects.

Coming back to coding. Today AI already takes over part of that load: it can relieve me of the necessary but non-creative work of converting intention into form. And here a shift happens that interests me the most:

I stop delivering lines of code, I start delivering intention.

What matters more becomes why I’m doing something and whom it serves. The intellect returns to its place as a tool, not as an identity.

But isn’t that a risk of going soft? If you have validations “on demand,” then why do you need your own falsification?

It depends on the domain. In the technical space the validator is merciless: something works or it doesn’t. In soft domains it’s harder. That’s why in perspective engineering the key thing for me is a practical criterion: before I accept something as sensible, I look for independent sources and check the quality of the evidence. Meta-analyses, samples, context of the authors, compatibility with experience, but also whether a given view is merely an attractive narrative.

And it is here that AI can shorten the distance from intention to form. Thanks to that, I have more attentional resources for meaning, for relationships, for course correction. This isn’t handing over the wheel — it is reclaiming space.

All right. But what does this change culturally? What’s in it for the community?

If thinking becomes a service, then what’s scarce changes. In the world of cheap intelligence, the ability to tolerate discomfort and course-correct — that is, responsibility — becomes more expensive. And then the carrier of rank becomes intention rather than efficiency. Not in the sense of a moral label, but as a force organizing the system: what do you choose? what do you omit? whom is it meant to serve? what price do you accept, and what price no longer?

This is the main turn for me: less “who is right,” and more “who can answer the call of the situation without deceiving themselves and without trampling others.”

And what is the significance of this discomfort?

It’s a shorthand. The point is that in practice, tolerance of a certain level of discomfort translates into the ability for introspection, and thus into inner honesty, which is the precondition for correcting beliefs or behaviors. When some facade falls away, for some people that means confronting false beliefs about themselves, and that always carries a certain dose of natural discomfort understood very organically, as a passing psychic tension.

You keep bringing up intention as a force organizing the system, not a moral label. If you had to show in one image how the structure of financing can distort intentions.

We can imagine a situation: someone builds a social-media platform, and after years it turns out that its design harms users’ psyches. It promotes harmful content to attract attention. Otherwise revenue drops and investors stop funding the project. Not because the creators “wanted evil.” More often because they felt an inner deficiency and poverty, and later also because the company grew from a dozen people to hundreds or thousands, and by going public acquired an obligation to increase profits. Then profit became the highest good. This shows intention precisely not as a moral label, but as a force organizing the system: the funding structure rewards profit, and profit can distort intentions even without explicit will to harm.

As I’m answering this question, a lawsuit has just been filed in the US against social media platform owners for causing psychological harm. A user identified by the initials KGM alleges that when she used the platforms as a child, the content presented to her negatively affected her well-being, contributing among other things to anxiety disorders and suicidal thoughts.

How can AI help solve this problem?

It’s already happening. I increasingly see LLMs beginning to displace the internet’s know-it-alls — those we once followed because they had an opinion on every topic and always sounded confident. What’s more, in certain areas they are even replacing close ones or friends, especially where sensitive things are involved: shame, fear, guilt, ambiguous motives. This is practical, because the model is available instantly, but it is also culturally significant: if the user shifts attention from the feed of a social medium to a conversation, the attention economy changes.

I suspect this must now be causing concern wherever attention is currency: in the marketing departments of social media platforms that for years designed their architecture so that we would come back to them for emotional stimulation, not for genuine self-understanding.

In a conversation with a model, part of the social stakes disappears. You don’t have to win in front of an audience, don’t have to defend your image, don’t have to manage belonging to a clan — which in social media activates almost automatically. This creates what I would call a safer field.

The internet shortened social distance by letting us meet people from the other side of the world who think similarly. But AI shortens it differently: it gives access to rare perspectives without the need to seek out their carriers. It is like a cultural condensate — a sample that can intrigue you, name an experience. You don’t have to make mistakes and backtrack when you realize that the perspective you adopted isn’t actually compatible with your character, doesn’t serve it. It saves time.

But there is also potential for more fundamental shifts.

What kind?

In the optimistic scenario, the cultural change initiated by AI may shift the emphasis toward intention. And by that I don’t mean only the pious wishes connected with the social effect of dethroning the intellect — though those too — but very practical scenarios.

If “cheap intelligence” lowers the barrier to entry, pluralism emerges: more small platforms, more niche communities, more alternatives. Then user well-being can become more important than investor profit — not because of a conversion of corporatism, but because competition grows. And the axis of that competition, once intermediaries are cut short, is precisely intention.

Further, if pluralism is to be the remedy, a new organ of orientation must also emerge. Because in a polyversal world, the problem isn’t the lack of information but its excess. And here AI can step into a role that sounds modest but is crucial: an intention filter on the user’s side.

I imagine agents working for users: not as sole advisors, but as guides through the thicket. A swarm of tools that examines the properties of a system (a platform, a community, a source), and knowing your values and needs suggests: “this will strengthen you,” “this will unsettle you,” “this is clever but feeds on emotions.”

The condition for honesty is simple: the agent must be able to say why it filters that way. What criteria did it adopt? What is its interest and how is it meant to serve us? Without that, the filter becomes just another form of propaganda.

If such a swarm is only supposed to filter and suggest, then where in your view does the boundary lie between a guide through culture and someone who co-creates that culture — and what happens when we start blurring that boundary?

AI doesn’t create culture directly; it doesn’t introduce novelty — at least not yet. We might have that impression, because there has never before been a moment in history when a single person conversed with an averaged billion people compressed into a single shape.

Besides, even the best agent is a filter and an amplifier: it can help select, but it doesn’t itself bear consequences on the other side of the relationship. And culture is precisely that network of consequences.

You say AI “doesn’t create” culture. That sounds like a provocation. What do you mean?

When we look at this systemically, LLMs and diffusion models are not a new “author of culture” in the primary sense. They perform a lossy compression of existing human artifacts — language, images, thinking habits — into a digitally represented multidimensional space in which one can conveniently interpolate between points. It is like a shared dictionary, but written not in definitions, but in weights and statistics.

And what happens when such a mechanism becomes a tool of everyday use?

In culture, three things start happening at once: averaging, colonialism, and the disappearance of detail.

Let’s start with averaging. Why does this matter culturally at all?

Models are trained to minimize errors. And in practice, an “error” is often whatever deviates from the pattern: the strange, the sharp, the unpredictable, the style-breaking. During fine-tuning (e.g. RLHF), extremes are naturally smoothed out. This has a clear advantage — less violence, less toxicity — but a side effect is that it cuts out some of the “high cultural frequencies”: genius, risk, madness, non-obviousness, absurdity, and fresh paradox.

Meaning?

The aesthetic turns beige. Prose becomes smooth, poetry bland, morality proper. This isn’t the result of bad will, but rather of the objective function: when everyone plugs into the same smoothing tool, the system’s variance drops. And culture lives precisely on variance, on entropy. And by culture I don’t mean just art or convention, but the clouds of values we absorb by being among others, which influence how we think and behave. These values are transmitted above all by example, not by readings or works of art.

You say “colonialism.” Sounds like a heavy accusation.

It is more a description of the mechanism of training networks and parameterizing them. A model’s weights are frozen decisions about what is “typical,” “beautiful,” “professional,” “normal.” When you ask a model for a “beautiful house” or an “elegant outfit,” you get an answer that isn’t neutral. It is statistical — and therefore culturally embedded in the data the model was trained on. If Western and Anglophone perspectives dominate, then local nuances become noise that the filter discards.

What’s most dangerous about this?

Hidden power, but sewn in deeper than in movies or advertisements, because it is built into the tool with which a person thinks and creates. You don’t have to convince anyone; it’s enough that the result is easier, faster, and looks better. You can have something instantly, but when you’re not attentive and precise, you pay for it with conformism.

And the disappearance of detail? That already sounds quite technical.

Yes, and that’s exactly why it is insidious — unnoticeable immediately, only after a longer time. The internet is being flooded with synthetic content, and new models are beginning to learn from data generated by old models. It is a photocopy of a photocopy: with each cycle we lose details, deviations, anomalies — the fuel of innovation.

Can this be named more precisely?

One can speak in the language of entropy in the information-theoretic sense: if rare signals disappear from circulation, the distribution becomes more predictable, and the model increasingly proposes what already was. Digital culture, like Ouroboros, begins to eat its own tail. But it is worth mentioning the curious fact that entropy can also be understood existentially…

In considerations about consciousness? Being?

Indeed. In Shannon’s framework, entropy is a measure of uncertainty in a signal; less entropy means greater predictability. But in considerations about consciousness, one also encounters the intuition that less “cognitive noise” can correlate with a greater sense of meaning. Bernardo Kastrup favors this line of thinking: when the narrative, or even broadly the epistemic apparatus of the mind quiets down, experience can become more coherent, even though it is poorer in content as measured by neural activity. The habit of incessant self-commentary weakens — the same one that neuroscience associates with the default mode network — and an experience of “meaning without description” appears.

And here hope emerges?

Yes. In this arrangement, the human ceases to be merely a craftsman of text. They begin to serve as a source of entropy — not in the sense of chaos, but in the sense of novelty. AI excels at interpolation. It is worse at extrapolation, at going beyond the map. A biological, sentient subject — rooted in pain, joy, absurdity, and relationship — can inject into the system something that isn’t just another version of the same.

So, practical advice?

Simple:

Preserve your quirks!

In the age of a cultural low-pass filter, anomalies become a precious resource.

The interview above was conducted with me by the language model GPT-5.2, which asked me several hundred questions, of which 20% required longer answers expressing opinions, while the rest were multiple-choice tests designed to sequence threads and clarify ambiguous statements.

Where a sentence had syntactic or stylistic flaws and needed correction (approx. 3% of the text), the model drew on a previously created idiolectal profile of my person containing approximately 250 dimensions characterizing my writing style and communication patterns. The profile was based on a prior analysis of approximately 1,500 machine pages of materials I had written, as well as on our earlier conversations.

Editorial review before publication was carried out by Claude Opus 4.6.