Clojure, like every Lisp dialect, comes equipped with an interactive console that lets us experiment and test our knowledge in real time. Before we move on to the theoretical foundations of the language, let us get some hands-on contact with its mechanisms.

First Steps

Clojure is a Lisp that runs on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). This means that the fundamental elements of the language are implemented in Java, and compiling Clojure programs produces bytecode files that can be run using the JVM. One could say that Clojure is written in Java, yet it differs from Java in syntax and grammar.

In certain contexts Clojure behaves like an interpreted language, because a substantial part of a program’s source code is compiled into bytecode at load time by the Clojure compiler, rather than ahead of time. The resulting bytecode can then be further optimized into native machine code by the JVM’s JIT compiler (just-in-time compiler). This runtime compilation model allows the language to take full advantage of its dynamic nature.

Installation

A popular way to install Clojure is to use the Leiningen script. A Java runtime environment is required for it to work correctly.

Leiningen is a tool that lets you quickly initialize projects. Their dependencies on

additional components (programming libraries as well as the version of Clojure

itself) can be specified using a project.clj configuration file placed in the

project directory.

To use Leiningen on Unix-like systems, the best approach is to create a bin

subdirectory in your home directory (if it does not already exist) and to add a

PATH variable assignment to your shell startup file (e.g., .profile) so that this

path is also searched:

if [ -d "$HOME/bin" ] ; then

PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"

fi

Then we can download and install a stable release of the tool:

1[ ! -d "$HOME/bin" ] && mkdir "$HOME/bin"

2

3wget -O ~/bin/lein \

4 https://raw.github.com/technomancy/leiningen/stable/bin/lein && \

5 chmod 755 ~/bin/lein && ~/bin/lein upgrade

[ ! -d "$HOME/bin" ] && mkdir "$HOME/bin"

wget -O ~/bin/lein \

https://raw.github.com/technomancy/leiningen/stable/bin/lein && \

chmod 755 ~/bin/lein && ~/bin/lein upgrade

CLI and deps.edn

Since 2018, a sensible alternative to external tools like Leiningen has been to use the mechanisms already present in the distributed language packages:

- the

clojurecommand for running programs, - the

cljcommand for interactive work, - the

deps.ednfile for specifying a project’s dependencies.

One should, of course, start by installing the language itself, which will look different depending on the operating system. Instructions can be found in the Getting Started section of the official Clojure website.

It is worth noting that on GNU/Linux distributions, installation via the system’s package manager and packages prepared by the distribution maintainer (e.g., DEB or RPM) may be somewhat outdated: some commands may be missing and some options may not be supported. It is therefore best to use the official installation script from the language’s website.

The macOS release can be found in the Brew package repository (installation is

trivial and amounts to running brew install clojure). Windows users can refer

to the “clj on

Windows”

installation guide.

The mechanism based on deps.edn differs from other popular dependency tools in that

the configuration file contains only data, not function or macro invocations.

The edn extension is short for EDN (Extensible Data Notation). It is based

on S-expressions and was created by the people developing the Clojure language. In

fact, EDN is a subset of Clojure syntax. One can think of this format as a safe way

of storing data used by programs – safe in the sense that none of the data will

accidentally be treated as code to be executed.

See also:

REPL

In Clojure, software development most often involves working with the language’s interactive console known as REPL. It is essentially a loop of three successive processes:

- reading source code,

- evaluating the expressions found, and

- printing the results of computations.

Its full name is read–eval–print loop (REPL).

Thanks to REPL we can write test programs and debug existing ones while having direct access to all global identifiers – names of functions, values of global variables, or Java classes.

In Lisp dialects the REPL often serves as the primary tool for developing software. This way of working is called interactive programming.

The standard input, output, and diagnostic output of a REPL need not be a real or virtual terminal device alone – they can also be a Unix domain socket or a TCP/IP socket. Thanks to the nREPL protocol, popular editors such as Emacs (via CIDER), Vim (via Conjure or vim-fireplace), or VS Code (via Calva) can be integrated with a REPL console running as a daemon.

To start a REPL session, we can use Leiningen in this mode (the command lein repl)

or Clojure’s built-in client (the command clj).

See also:

Reading and evaluating

If we strip the interactive element from REPL, the process of running a Clojure program can be divided into two main stages (discussed in detail in the next chapter):

- reading and

- evaluating.

In the first stage, data is fetched from disk or standard input and checked for syntactic correctness. This is done by a component called the reader. If the syntax is correct, the expressions found in the program are transformed into corresponding in-memory objects that represent source code in a form the compiler can understand.

But that is not all, because the prepared data representing the program must be put to use and interpreted semantically. At this point the evaluator takes over, processing the structures placed in memory and attempting to evaluate them.

Working with the console

Let us try to get acquainted with the language’s interactive console using the

command lein repl or clj:

lein repl

lein repl

After launching, we should see output similar to the following:

nREPL server started on port 50718 on host 127.0.0.1 - nrepl://127.0.0.1:50718

REPL-y 0.3.7, nREPL 0.2.12

Clojure 1.9.0

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM 10.0.2+13

Docs: (doc function-name-here)

(find-doc "part-of-name-here")

Source: (source function-name-here)

Javadoc: (javadoc java-object-or-class-here)

Exit: Control+D or (exit) or (quit)

Results: Stored in vars *1, *2, *3, an exception in *e

user=>

nREPL server started on port 50718 on host 127.0.0.1 - nrepl://127.0.0.1:50718

REPL-y 0.3.7, nREPL 0.2.12

Clojure 1.9.0

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM 10.0.2+13

Docs: (doc function-name-here)

(find-doc "part-of-name-here")

Source: (source function-name-here)

Javadoc: (javadoc java-object-or-class-here)

Exit: Control+D or (exit) or (quit)

Results: Stored in vars *1, *2, *3, an exception in *e

user=>

The last line (user=>) is the so-called REPL prompt. It signals readiness to

accept textual expressions from standard input. The label user is the name of the

current namespace – a special map of bindings that we will discuss later.

A simple example

Let us start as simply as possible by typing the following text in the REPL console:

123 ; a numeric literal

;=> 123

123 ; a numeric literal

;=> 123

We entered the number 123 and in return received the same value. On the surface very little happened, yet the REPL console completed a full cycle of its loop. Let us trace what occurred:

-

We entered a line of text containing source code.

-

By pressing ENTER we caused the line to be sent to the standard input of the reader (the component responsible for syntactic analysis of the program text), which began processing it.

-

The reader analyzed the line and isolated from it the so-called lexemes, i.e., constructs with syntactic significance:

123and;. It found no marker that would require waiting for the next line before continuing the analysis. -

The reader recognized the following kinds of lexemes (so-called tokens):

- numeric literal (

123), - comment (

;and all characters to the end of the line).

- numeric literal (

-

During the parsing stage:

- the literal

123was recognized as a so-called symbolic expression, - the comment was ignored.

- the literal

-

The reader created an in-memory representation of the source code in which the expression

123is represented by a datum of typejava.lang.Longholding the value 123. -

The evaluator (the component responsible for semantic analysis of the program) took over.

-

The evaluator began evaluating the objects placed in memory by the reader by calculating their values.

-

The expression 123, represented by the

Longtype, was recognized as a so-called constant form – an object that represents its own value. -

The evaluator passed the result of the computation to the function that prints results.

-

The print function converted the integer value 123 into its textual representation – a numeric literal – and, together with a newline character, sent it to the REPL console’s standard output.

Let us try something more sophisticated:

(print 123) ; a function call

; >> 123

(print 123) ; a function call

; >> 123

We can see a construct familiar from other programming languages: print, which is

used for displaying values on screen.

In Clojure (print 123) is syntactically a so-called symbolic expression

(S-expression), more precisely a list symbolic expression in which print is the

name of a function and 123 is the value of the argument passed to its

invocation. The parentheses mark the beginning and end of a list of elements

comprising the name and arguments (operator and operands).

To invoke functions we use a so-called function-call form. A form is an expression that represents valid program code in Lisp. Valid code is one that can be executed in order to compute a value. A function-call form, as the name implies, is therefore a construct used to invoke existing functions in order to obtain results and/or side effects (as in this case: printing to an output device).

The term “form” is rooted in the early dialects of Lisp and indicates that we are dealing with a datum that can be subjected to evaluation. In Lisps, source code is also (read-in) data, but not all of that data will require computation.

Returning to the syntactic level, in our example the elements of the list expressing the program code are:

- the symbol

print, - the numeric literal

123.

Before Clojure can determine that we are dealing with a function call, however, it

carries out several steps to find out where to look for the callable identified by

the symbolic name print and what it is. (Besides functions, so-called macros and

special forms can also be invoked.)

The text print, syntactically speaking, is a symbol – represented internally,

right after the program text is read into memory, by a value of type

clojure.lang.Symbol. The numeric literal 123, in turn, is an integer value

(internally expressed as a datum of type java.lang.Long).

When the compiler encounters a list whose first element is a symbolic label, it tries to determine what kind of invocation it is dealing with. To this end it attempts to treat the symbol placed in the first position as a so-called symbol form.

A symbol form is a symbol that names (identifies) some value or callable (e.g.,

a function). It resembles a variable or function name in other

languages. Syntactically it is a human-readable label that refers to some existing

construct because it was previously bound to it. In this case what lies behind the

name print is being checked. A symbol form is thus a symbol that, during the

name-resolution process, can be resolved to some other object (not necessarily

a function).

The symbolically expressed name print will therefore be looked up in several

internal areas to find the object it identifies. If this succeeds, and moreover

print turns out to be a function, the enclosing construct will be recognized as its

invocation form.

In our case the binding of the symbolic name print to a function object will be

found in a special map called a namespace. The key will be a datum of type

clojure.lang.Symbol with the value print, and the associated value will be a

special object of type clojure.lang.Var. The latter will contain a reference to the

function’s code – an object of type clojure.lang.Fn.

Why doesn’t print refer directly to the function object? This has to do with the

design of the Clojure language, its approach to concurrent execution, and the

handling of immutable data. The intermediary Var object provides appropriate

isolation and a value-update strategy when the program consists of multiple

concurrently executing threads.

Once the compiler has established that print refers to function code, the entire

list S-expression will be treated as its invocation. This means that every subsequent

element of the list (in our case 123) will become an argument whose value is to be

passed at the time of invocation.

It is worth noting that when Clojure evaluates a symbolic expression that turns out

to be a function-call form, it eagerly evaluates each argument being passed. In this

case the value 123 (of type java.lang.Long) will not be further evaluated, because

it will be recognized as a so-called constant form – one whose value does not

change during evaluation.

Constant forms include not only values (normal forms) but also expressions whose evaluation has been deliberately suspended using so-called quoting (quote forms).

At this point we know roughly 80% of Clojure’s syntax and 90% of the syntax of Lisps in general. Well done!

Note: Because Clojure is implemented in another high-level language, most syntactic constructs that are processed are already evaluated at the stage of reading and recognizing valid expressions. This does not mean that knowledge about subsequent processing stages is irrelevant; however, it is worth bearing in mind that the process involves far-reaching optimizations. In practice, therefore, some phases of translating the read-in program are carried out instantaneously, relying on the existing mechanisms of the host language (JVM).

Comments

Looking at the examples given earlier, we can see that by using a semicolon (;) we

are able to annotate the textual form of a program with comments. Comments are

ignored during program execution and allow us to illustrate code with intelligible

explanations.

In subsequent examples we will use comments containing an arrow to show computation results displayed by the REPL, while comments beginning with a double greater-than sign will show data printed by programs.

; =>– computation results,; >>– standard output.

Abstraction levels

While discussing the earlier example we may encounter different terms used in

reference to the same program elements. First we call the fragment 123 a literal,

then a symbolic expression, and finally a form. This stems from the different

abstraction levels used when talking about a program, which are rooted in the

successive stages of translating it from its textual form into an executable (and

even executing) one.

To make it easier for us to use the terminology that describes programming in Clojure (and other Lisp dialects), it is worth studying the table below, which illustrates the concepts that appear at various abstraction levels – from concrete constructs to the most abstract ones.

| Unit | Description | Level |

|---|---|---|

| Character sequence | Source code in textual form | Textual |

| Lexeme | a fragment of program text recognized as a known lexical construct | Lexical |

| Symbolic expression | An isolated syntactic element expressing a value or operation | Grammatical |

| Form | An expression whose value can be computed | Semantic |

| Value | The result of computing an expression | Data |

Let us try to break down a slightly more complex program in this way:

| Notation | Unit | Level |

|---|---|---|

(+ 2 2) |

Source code | Textual |

( + 2 2 ) |

List literal (start) Symbol Numeric literal Numeric literal List literal (end) |

Lexical |

+ 2 2 |

Symbolic expressions (atomic) | Grammatical |

( + 2 2 ) |

Symbolic expression (list) composed of atomic expressions |

Grammatical |

+ [type Symbol] 2 [type Long] 2 [type Long] |

Symbol form (identifier) Constant form (self-evaluating) Constant form (self-evaluating) |

Semantic |

(clojure.core/+ 2 2) |

Function-call form Argument list form |

Semantic |

| 4 | Value returned by the function | Data |

The individual levels correspond to successive stages of processing source code:

-

At the textual level we are dealing with a character sequence representing source code.

-

At the lexical level the character sequence is read in and its lexical units are recognized – for instance, numbers, symbols, list-opening and list-closing markers, etc.

-

At the grammatical level we deal with parsing, i.e., creating an in-memory structure that represents expressions using appropriate data types; for example, a compound list expression will be represented by a list (type

PersistentList) whose individual elements are data of typeSymbol(symbols) and integers (typeLong). -

The semantic level is associated with the phase of computing expression values that reside in memory. This is where forms are detected – for example, symbols pointing to other objects, function calls, and constant values are recognized.

-

At the data level we are dealing with the results of computations produced during the evaluation of forms.

Creating an application project

Let us try to write a simple program that we can run both under the REPL console and without it. Leiningen will come to our aid, as it is equipped with a command for creating application skeletons.

Instead of manually creating the project structure and describing dependencies with a

deps.edn file, we will use the Leiningen tool, because by examining its settings we

will learn more about commonly used data structures and Clojure language constructs.

Let us issue the following command in the interactive shell’s command line:

lein new app shopping

lein new app shopping

A subdirectory called shopping containing the project files will be created in the

current directory, and we will see the following message on screen:

Generating a project called shopping based on the 'app' template.

In the directory we will find the following files and directories:

| Name | Purpose |

|---|---|

CHANGELOG.md |

A Markdown text file for keeping a changelog |

LICENSE |

Licensing information for the project in text form |

README.md |

A Markdown text file describing the application |

project.clj |

A Clojure source file containing Leiningen settings |

doc |

Documentation directory |

resources |

Directory for additional resources (e.g., CSV files, images, etc.) |

src |

Directory containing the application’s sources |

test |

Directory containing the application’s automated test sources |

Initially, the project.clj file will look roughly like this:

project.clj

1(defproject shopping "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT"

2 :description "FIXME: write description"

3 :url "http://example.com/FIXME"

4 :license {:name "Eclipse Public License"

5 :url "http://www.eclipse.org/legal/epl-v10.html"}

6 :dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.8.0"]]

7 :main ^:skip-aot shopping.core

8 :target-path "target/%s"

9 :profiles {:uberjar {:aot :all}})

(defproject shopping "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT"

:description "FIXME: write description"

:url "http://example.com/FIXME"

:license {:name "Eclipse Public License"

:url "http://www.eclipse.org/legal/epl-v10.html"}

:dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.8.0"]]

:main ^:skip-aot shopping.core

:target-path "target/%s"

:profiles {:uberjar {:aot :all}})

It is easy to see that we are dealing with Clojure source code. What is its purpose? When Leiningen performs certain tasks (e.g., launching an interactive REPL console or building a software package), it needs to be configured at least minimally. This configuration will include, for example, such basic parameters as the application name or licensing terms. The tool’s authors decided that instead of storing settings in some specialized format, they would use the Clojure language syntax. The settings file is therefore read from the given project’s directory during a Leiningen work session.

Before we move on, let us open the project.clj file in a text editor and adjust its

contents a little:

project.clj

1(defproject shopping "1.0.0"

2 :description "Shopping list"

3 :url "https://randomseed.pl/"

4 :license {:name "GPL"

5 :url "https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html"}

6 :dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.9.0"]]

7 :main ^:skip-aot shopping.core

8 :target-path "target/%s"

9 :profiles {:uberjar {:aot :all}})

(defproject shopping "1.0.0"

:description "Shopping list"

:url "https://randomseed.pl/"

:license {:name "GPL"

:url "https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html"}

:dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.9.0"]]

:main ^:skip-aot shopping.core

:target-path "target/%s"

:profiles {:uberjar {:aot :all}})

Common constructs

With a useful fragment of Clojure source code before our eyes, let us try to use it as an introduction to the basic language constructs.

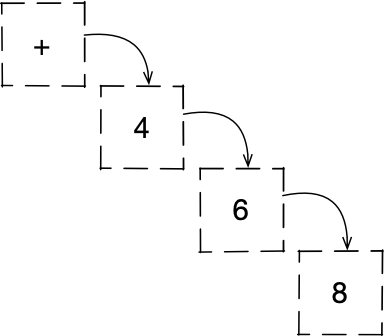

List S-Expressions

The first line, which opens with a parenthesis, begins a so-called list S-expression – a symbolically expressed list of elements. Here is a simpler example of such a symbolically written list expression:

(+ 4 6 8)

(+ 4 6 8)

In Lisp dialects this kind of syntactic construct has a special meaning. Its first element is the identifier of the callable that will be invoked.

Symbolic expressions can be nested:

(+ 4 6 (* 2 4))

(+ 4 6 (* 2 4))

It is worth mentioning that we can also speak of so-called atomic S-expressions,

which are not collections of elements but single constructs. In the example above +

is an atomic S-expression (or atom for short), as are the numeric literals 2 and

4. In the project.clj example, defproject is likewise an atomic S-expression.

Because of its position in the list, defproject will be treated as the name of a

callable which – as we can guess – was defined in the Leiningen tool as a function

or macro.

Symbols

The text defproject is a so-called symbol. Symbols in Clojure are the

equivalent of keywords, function names, and variable names in other languages. They

serve to identify values and other objects, to give them names.

During the phase of reading source code into memory, defproject will be internally

represented by the data type Symbol (more precisely clojure.lang.Symbol). But

that is not the end, because immediately afterwards (during the expression-evaluation

stage) it will be replaced by the value previously assigned to it (e.g., a number,

string, function object, macro, etc.). Used in this way it will be a symbol form,

which helps us use human-readable labels in reference to data.

The fact that we can use symbolic names in programs is owed to the special treatment of symbols by the compiler. Whenever a symbol form appears in the code, the language mechanisms will attempt to obtain the value bound to it, in order to substitute that value in place of the symbol and continue evaluating expressions.

In the given example not only defproject is a symbol – so is the text shopping,

although their roles are somewhat different.

Thanks to symbols we can name all sorts of objects, but later we will see that there are also ways to use them as ordinary values rather than identifiers. In such forms they find application primarily when creating syntactic macros, which are used to modify a program’s source code by the program itself.

Invocation arguments

The remaining elements of the list S-expression (up to the closing parenthesis) are

arguments that will be passed to the defproject invocation. The first one is

also a symbol, but what value will it express?

In our case the symbol shopping will be used literally to name the project. It will

not be recognized as a symbol form; instead it will be treated as a specifically

expressed project name.

Functions and macros

At this point we can be certain that defproject is a macro. Why?

In Clojure, two primary top-level constructs let us define globally named invokables: functions and macros.

Functions accept sets of constant values and, after performing computations on them, return a value or a multi-valued structure. If a symbol appears in the position of a function’s argument, it will be treated as a symbol form and subjected to the process of resolving the value to which it is bound. Only that value will be passed to the function call.

Macros also accept arguments, but unlike functions, the values of those arguments are not computed before being passed. This means that a macro operates on data structures representing S-expressions placed in argument positions, not on the values of those expressions. It processes data describing fragments of source code.

If a macro’s argument is a symbol, a datum of type Symbol will be passed, not the

value indicated by that particular symbol. Of course, nothing prevents one from

manually resolving a symbol’s value or evaluating another kind of expression inside

the macro but that would be impractical since macros operate before a program starts

running.

The values returned by macros are S-expressions that will appear in the code in place of the macro invocations and will be further evaluated. In this way a program can modify its own code.

Let us consider two calls – of a function a-function and a macro a-macro:

(a-function humpty (dumpty sat wall))

(a-macro humpty (dumpty sat wall))

(a-function humpty (dumpty sat wall))

(a-macro humpty (dumpty sat wall))

The first invocation is syntactically correct but not semantically – an attempt to

obtain a value, even if the function a-function exists, will end in an error. Why?

The symbols humpty, sat, and wall have not been previously bound to any values,

and the symbol dumpty does not identify any function or macro, even though it

occupies the first position of a list S-expression. This is therefore a Lisp form but

not a valid Lisp form.

The second invocation has a good chance of executing correctly, because the argument

values passed to the macro a-macro will be in-memory representations of

S-expressions: the symbol humpty (represented by an object of type Symbol) and

a list of the symbols dumpty, sat, and wall (represented by an object of type

PersistentList).

If defproject in our configuration file were a function, then a binding of the

symbol shopping to some value would have to exist beforehand. We can therefore say

with high probability that we are dealing with a macro.

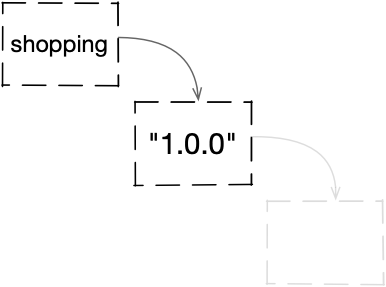

Strings

The next argument of the defproject invocation is the string 1.0.0. Its

literal can be recognized by the surrounding quotation marks. In Clojure, strings are

represented by objects of type java.lang.String.

Here the string specifies the version of our project.

Keywords

The further arguments passed to the defproject macro invocation exhibit a certain

regularity: every other element is preceded by a colon (:). This character has

special lexical meaning in Clojure, and labels written in this way become

keywords.

A keyword in Clojure is an object of type Keyword. It resembles a symbol, but

serves as an identity builder for utility structures in programs rather than

values in source code. During program evaluation, symbols are recognized as symbol

forms and transformed into the values bound to them, whereas keywords are

not. A keyword’s value is itself; moreover, two keywords with the same name are

represented by only one object in memory (on JVM).

In the case of project.clj, keywords play the role of configuration parameter

names, and the elements paired with them express the values of those parameters:

| Parameter identifier | Meaning |

|---|---|

:description |

Brief description |

:url |

Application website URL |

:license:name: url |

License information map License name License URL |

:dependencies |

Dependency vector |

:main |

Main function |

:target-path |

Target path |

:profiles:uberjar:aot |

Profiles map Uberjar profile map AOT compilation setting |

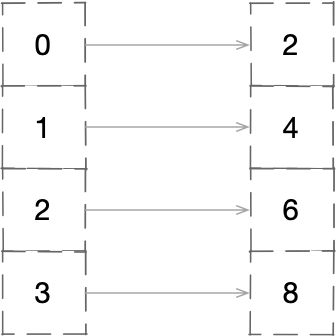

Vectors

The table introduced two interesting terms: vector and map. Let us start with the

vector. It is a data structure (of type PersistentVector) resembling arrays

known from other programming languages – we are dealing with a collection whose

elements are ordered and indexed using natural numbers. We can therefore quickly

access any given element by specifying its number (starting from 0).

In the case of the :dependencies parameter, which denotes dependencies, the value is

a vector, which in Clojure can be expressed using a literal consisting of square

brackets. In this syntactic form we can also call it a vector S-expression.

Here is a simpler example of a vector S-expression, which is a symbolic representation of a vector:

[2 4 6 8]

[2 4 6 8]

In our project definition file the vector has only one element, which is another vector:

[[org.clojure/clojure "1.9.0"]]

[[org.clojure/clojure "1.9.0"]]

This is because there can be many dependencies. Each one is expressed as a pair of values in a vector S-expression.

In our example the first (and only) nested vector has exactly two elements. In this

way we communicate that our application requires the org.clojure/clojure component

in version 1.9.0 to work correctly.

It is worth noting that the first element is also a symbol serving a utility rather than syntactic purpose – it specifies the name of a software package from the Maven Central Repository so that Leiningen can download it. The package in question is the Clojure language in the indicated release. If we are curious, we can search the Maven repository ourselves using its web interface.

Maps

Another construct worth mentioning is the map. A map is an associative data

structure represented in Clojure by objects of type PersistentMap or

PersistentArrayMap (for shorter collections). It allows us to pair up objects of

arbitrary types.

The elements of maps used for indexing are customarily called keys, and the objects assigned to them are called values. Maps resemble associative arrays and dictionaries known from other programming languages:

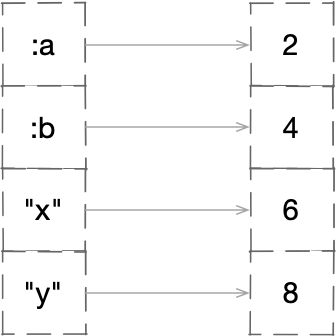

{:a 2 :b 4 "x" 6 "y" 8}

{:a 2 :b 4 "x" 6 "y" 8}

In the defproject invocation a map appears in the form of a map S-expression,

represented by a literal composed of curly braces with pairs of elements placed

inside:

{:name "Eclipse Public License"

:url "https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html"}

{:name "Eclipse Public License"

:url "https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html"}

In our project definition the map is used to express licensing information and

so-called profile settings. The first pair assigns the key :name to a string

containing the license name, and the second assigns the key :url to a string

representing the URL where the reuse terms can be found.

Further in the defproject invocation we can also notice that values placed in maps

can themselves be other maps – in which case we are dealing with nested structures.

Main program file

In the src subdirectory of the project skeleton created by Leiningen we will find a

subdirectory called shopping, which contains the file core.clj with the following

contents:

src/shopping/core.clj

1(ns shopping.core

2 (:gen-class))

3

4(defn -main

5 "I don't do a whole lot ... yet."

6 [& args]

7 (println "Hello, World!"))

(ns shopping.core

(:gen-class))

(defn -main

"I don't do a whole lot ... yet."

[& args]

(println "Hello, World!"))

The first two lines form an S-expression in which the built-in Clojure macro

identified by the symbol ns is invoked. Two arguments are passed to the invocation:

shopping.core– a symbol,(:gen-class)– a list S-expression containing a keyword.

Namespace

The ns macro is used to set the current namespace and to create one if it does not

yet exist.

Namespaces enable the grouping of globally visible identifiers in order to eliminate conflicts. If we wanted to use two external libraries in a program, both of which defined functions with the same name but entirely different purposes, a conflict would arise or an identifier from the library loaded earlier would be shadowed. Namespaces solve this problem, because we can refer to a function by specifying not only its name but also the namespace to which the name was assigned.

In the case of Clojure, namespaces are internally maps in which we can place

references to data of any type (including individual values, collections, and

functions). The keys of these maps are symbols, and the values are global variables

(type clojure.lang.Var) or Java classes.

In our program the ns macro creates the namespace shopping.core and sets the

special dynamic variable *ns* so that within the source code placed in the

core.clj file the default namespace is the one specified. As a result, when

resolving the value of every symbol form placed in the file, the set namespace will

be searched. If we placed, say, the symbol x in core.clj, then during its

evaluation the namespace shopping.core would be searched to find the object

associated with the symbol.

Pairs from other namespaces can be imported into a namespace. This is what happens

with the standard functions, macros, and special constructs built into Clojure. Every

newly created namespace contains the necessary entries unless the programmer

explicitly indicates otherwise. As a result we can refer to popular functions in

programs without specifying the namespace they come from – for example, we can use

(+ 2 2) instead of (clojure.core/+ 2 2). The latter form of the symbol is called

a namespace-qualified symbol.

The :gen-class notation in line 2 is one of the directives controlling the behavior

of the ns macro and means that during compilation to bytecode a Java class will be

generated for this namespace, and functions from this namespace whose names begin

with the - character will be represented as public methods. This makes it possible

to invoke Clojure functions from the Java virtual machine level.

Main function

In line 4 we see another S-expression:

src/shopping/core.clj

(defn -main

"I don't do a whole lot ... yet."

[& args]

(println "Hello, World!"))

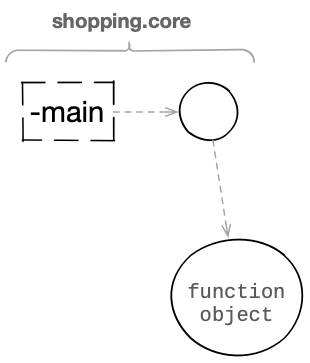

The form being invoked is defn, which in Clojure is a built-in macro for defining

named functions. The effect of the invocation is:

- The creation of a function object.

- The placement in the current namespace of a symbol bound to the function object.

The first argument of defn is the function name, which here is given by the

symbol -main. The leading hyphen-minus helps in automatically exposing the function

as a Java method.

In our case the current namespace is shopping.core. In the program we will

therefore be able to identify the function using the symbol form -main or

shopping.core/-main.

The next argument of the macro is a string. Placed in this position, it becomes a

so-called docstring – a human-readable description that can be displayed in the

REPL using the doc macro.

The next nested S-expression passed to the defn invocation is a literal

representation of a vector presenting the list of arguments accepted by the

function being defined. From the perspective of the function’s interior we will call

them parameters, and the construct itself the parameter vector.

In this case the vector contains two symbols: & and args. The first has a special

meaning and lets us treat the next one as a so-called variadic parameter – a

structure that will hold the values of optional arguments passed to the

invocation. In our case there are no mandatory arguments, so the collection

identified by the symbol args will contain the values of all passed arguments.

The last symbolic expression (println "Hello, World!") is the function body –

the code executed every time the function is called and the argument list is

applied. Within the body we can use the symbols given in the parameter vector and

perform computations on them. If the function body contains more than one expression,

the returned value will be the value of the last one.

The built-in function println always returns a nil value, but we use it for the side

effect it causes – displaying the textual form of the given arguments’ values followed

by a newline character.

We can change the function body so that a different text is displayed:

src/shopping/core.clj

1(defn -main

2 "Displays a greeting"

3 [& args]

4 (println "Hello, Lisp!")

5 (println "My arguments:")

6 (println args))

(defn -main

"Displays a greeting"

[& args]

(println "Hello, Lisp!")

(println "My arguments:")

(println args))

Running the program

Leiningen lets us run the program we created without launching the interactive console. Let us enter the project directory and issue the following command:

lein run

lein run

We should see on screen:

Hello, Lisp!

My arguments:

nil

The line displaying the passed argument values contains the text nil. This is a

special object that denotes an undefined value. It appeared because our function did

not receive a single argument. Let us try again, but this time pass some parameters

to the command:

lein run one two three

lein run one two three

This time we will see:

Hello, Lisp!

My arguments:

(one two three)

The parentheses indicate that internally the argument list is represented by a list

data structure – this is how the println function presents this kind of

collection. The arguments of the main method from the shopping.core class come

from the parameters of the lein run invocation and are passed by Leiningen as

strings.

Building a Java archive

One way of distributing Java applications – and that is what our program becomes after initial compilation – is to place all needed components in a Java archive (JAR) file. To build such an archive we need to issue the following command:

lein uberjar

lein uberjar

We will see diagnostic messages similar to the following:

Compiling shopping.core

Created shopping/target/uberjar/shopping-1.0.0.jar

Created shopping/target/uberjar/shopping-1.0.0-standalone.jar

We can now go to the target/uberjar subdirectory and try to run the program as if

it were a standalone Java application:

cd target/uberjar

java -classpath shopping-1.0.0-standalone.jar shopping.core

The -classpath parameter specifies the path to the defined classes, while

shopping.core is the Java class corresponding to the namespace in our program. The

result of the invocation should not differ from the previous one.

It is worth remembering that a program packaged this way contains all dependent packages, including the Clojure language runtime in the version we used, as well as the program’s source code. Clojure is a highly dynamic language and distributing programs with source code allows the Clojure compiler to perform load-time compilation tailored to the runtime environment. AOT (ahead-of-time) compilation is possible, but it may cause compatibility issues between Clojure versions and limits certain dynamic capabilities.

Interactive project work

The interactive REPL console can serve not only for testing ideas but also for

interactively developing existing programs. If we execute the command lein repl in

the project directory, we will see a message similar to the following:

REPL server started on port 58947 on host 127.0.0.1 - nrepl://127.0.0.1:58947

REPL-y 0.3.7, nREPL 0.2.12

Clojure 1.9.0

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM 10.0.2+13

Docs: (doc function-name-here)

(find-doc "part-of-name-here")

Source: (source function-name-here)

Javadoc: (javadoc java-object-or-class-here)

Exit: Control+D or (exit) or (quit)

Results: Stored in vars *1, *2, *3, an exception in *e

shopping.core=>

The first thing that catches the eye is a slightly different REPL prompt compared to

the earlier session. Now it points to the current namespace shopping.core. Let us

check whether we have access to the binding of the symbol -main to the function

placed in this namespace:

1-main

2; => #<Fn@76c99f2f shopping.core/_main>

3

4(-main)

5; >> Hello, Lisp!

6; >> My arguments:

7; >> nil

8; => nil

9

10(-main 1 2 3)

11; >> Hello, Lisp!

12; >> My arguments:

13; >> (1 2 3)

14; => nil

-main

; => #<Fn@76c99f2f shopping.core/_main>

(-main)

; >> Hello, Lisp!

; >> My arguments:

; >> nil

; => nil

(-main 1 2 3)

; >> Hello, Lisp!

; >> My arguments:

; >> (1 2 3)

; => nil

In the first line we placed only the symbol -main, which was recognized as a symbol

form whose value is a function object. It is the textual representation of this

object that we can observe in the REPL output on line 2.

Line 4 also contains the same symbol, but it is part of a function-call form because

it occupies the first position of a list S-expression. We will therefore see the

result of executing the function -main.

The last function call (line 10) also includes values that will be applied. As a result we will see the textual representation of their structure.

Reloading code

While working with the REPL console within a project, we may sometimes want the

environment to reflect changes made to source files. This does not happen

automatically, and the simplest way is to end the session and invoke lein repl

again. This can be frustrating, because starting the Java virtual machine and loading

the Clojure core are time-consuming processes. Fortunately, other, more efficient

solutions exist.

The easiest and fastest way is to use the built-in use function, which causes the

code of the indicated libraries to be loaded and the bindings present in their

namespaces to be copied into the current namespace. The first argument of the

invocation should be a literally expressed symbol with the name of the library to

load. When the value of the next argument is the keyword :reload, the operation

will be repeated even if the code has already been loaded before.

If the REPL console has not been launched yet, we use lein repl in the project

directory. At the same time, let us open the file src/shopping/core.clj in an

editor and make a small modification so that our main function looks a little

different, for example like this:

src/shopping/core.clj

(defn -main

"Displays a greeting"

[& args]

(println "Hello, Lisp!"))

If we now call the function in the REPL, we will not yet see the changes:

(-main)

; >> Hello, Lisp!

; >> My arguments:

; >> nil

; => nil

(-main)

; >> Hello, Lisp!

; >> My arguments:

; >> nil

; => nil

Let us try once more, but this time precede the call to our function with the use

construct:

(use 'shopping.core :reload)

; => nil

(-main)

; >> Hello, Lisp!

; => nil

(use 'shopping.core :reload)

; => nil

(-main)

; >> Hello, Lisp!

; => nil

Success! The use function caused the file src/shopping/core.clj to be re-read and

the symbol -main in the namespace shopping.core to be bound to the code of the

new version of our function.

How did the use function know where to look for the file? It relied on a convention

according to which the src subdirectory is searched to find a path of

subdirectories named the same as the dot-separated parts of the name, except for the

last part, which indicates the file name with a clj extension. For the symbol

shopping.core the sought path was therefore shopping/core.clj.

It is worth mentioning the notation 'shopping.core in the first line. The

apostrophe placed before the symbol name causes the notation to not be treated as

a symbol form whose value is the object bound to the symbol, but rather as a literal

symbol – a constant form. This is necessary because use is a function, and in

order to pass it a symbol rather than the value bound to it, we must disable its

special syntactic meaning. This technique is called quoting and will be discussed

in more detail later.

In the main function, besides removing a few lines, we also changed the docstring. Let us check whether the change is visible here as well:

(doc -main)

; >> -------------------------

; >> shopping.core/-main

; >> ([& args])

; >> Displays a greeting

; => nil

(doc -main)

; >> -------------------------

; >> shopping.core/-main

; >> ([& args])

; >> Displays a greeting

; => nil

Summary

Basic concepts

In this chapter several important terms appeared. Some are common to all programming languages, while others are specific to Clojure. Let us recall them:

- Reader

- the component responsible for reading and parsing source code

- Evaluator

- the component responsible for evaluating expressions stored in memory by the reader

- Form

- an expression whose value can be computed by the evaluator

- Source code

- a human-readable representation of a computer program

- List

- a data structure consisting of interconnected elements; used primarily to represent in memory the list S-expressions that reflect source code expressions after reading

- Literal

- a lexical unit that expresses a fixed value in source code; recognized in the early stages of the reader's work

- Map

- an associative data structure that allows unique (within the map) keys to be assigned to values

- Namespace

- a global map with a fixed name containing bindings of symbols to objects

- Symbol

- a human-readable identifier; used to name values, functions, and variables

- Symbolic expression (S-expression)

- a notation that allows expressing individual or compound collections of elements; used to organize source code

- Global variable

- a reference object of type

Varplaced in a namespace, identified by a symbol, and itself pointing to an arbitrary value in memory; used to name functions, program settings, and other global identities whose states change infrequently - Vector

- a data structure consisting of a list of elements whose positions are identified by index numbers

Helper functions

In the interactive REPL console environment we can use helpful, auxiliary constructs:

-

(doc name)displays documentation for the element with the given name; -

(find-doc fragment)works likedoc, but accepts a name fragment or a regular expression; -

(apropos fragment)returns a sequence of matching elements from all namespaces based on a name fragment or a regular expression; -

(javadoc class)for a given Java class or object, opens the documentation file in a browser; -

(source name)returns the source code of the invokable (e.g., function) with the given identifier; -

(pst)displays information about the stack trace.

Example expressions

To wrap up, let us try entering some more complex expressions in the REPL. Each will be accompanied by a comment briefly explaining what the construct in the listing does. At this point we do not need to know exactly how to use the given functions or macros in full – let us treat the examples below as an introduction to subsequent installments, where they will be described in more detail.

1;; undefined value

2

3nil

4; => nil

5

6;; incrementing by one

7

8(inc 3)

9; => 4

10

11;; nested operations

12

13(+ 1 2 3 (inc 1))

14; => 8

15

16;; lexical bindings

17;; of symbols to values

18

19(let [a 5

20 b 1]

21 (- a b))

22; => 4

23

24;; global binding

25;; of a symbol to a function

26

27(def greet

28 (fn [] "hey!"))

29; => #'user/greet

30

31;; calling the greet function

32

33(greet)

34; => "hey!"

35

36;; defining a named function

37;; using the defn macro

38

39(defn hello [] "hello!")

40; => #'user/hello

41

42;; calling the hello function

43

44(hello)

45; => "hello!"

46

47;; defining a function

48;; with closure over symbols

49;; bound lexically in the enclosing environment

50

51(def add-2

52 (let [a 2]

53 (fn [b] (+ a b))))

54; => #'user/add-2

55

56;; calling the add-2 function

57

58(add-2 6)

59; => 8

60

61;; defining a function

62;; with closure over symbols

63;; bound to the enclosing function's arguments

64

65(defn make-adder [x]

66 (fn [y] (+ x y)))

67; => #'user/make-adder

68

69;; calling make-adder

70;; to produce an adder that adds 10

71;; and assigning the returned function a global name

72

73(def add-10 (make-adder 10))

74; => #'user/add-10

75

76;; calling the add-10 function

77;; returned by make-adder with argument 10

78

79(add-10 2)

80; => 12

81

82;; a quoted symbol

83

84'a-literal-symbol

85; => a-literal-symbol

86

87;; a quoted list S-expression

88

89'(+ 2 2 three)

90; => (+ 2 2 three)

;; undefined value

nil

; => nil

;; incrementing by one

(inc 3)

; => 4

;; nested operations

(+ 1 2 3 (inc 1))

; => 8

;; lexical bindings

;; of symbols to values

(let [a 5

b 1]

(- a b))

; => 4

;; global binding

;; of a symbol to a function

(def greet

(fn [] "hey!"))

; => #'user/greet

;; calling the greet function

(greet)

; => "hey!"

;; defining a named function

;; using the defn macro

(defn hello [] "hello!")

; => #'user/hello

;; calling the hello function

(hello)

; => "hello!"

;; defining a function

;; with closure over symbols

;; bound lexically in the enclosing environment

(def add-2

(let [a 2]

(fn [b] (+ a b))))

; => #'user/add-2

;; calling the add-2 function

(add-2 6)

; => 8

;; defining a function

;; with closure over symbols

;; bound to the enclosing function's arguments

(defn make-adder [x]

(fn [y] (+ x y)))

; => #'user/make-adder

;; calling make-adder

;; to produce an adder that adds 10

;; and assigning the returned function a global name

(def add-10 (make-adder 10))

; => #'user/add-10

;; calling the add-10 function

;; returned by make-adder with argument 10

(add-10 2)

; => 12

;; a quoted symbol

'a-literal-symbol

; => a-literal-symbol

;; a quoted list S-expression

'(+ 2 2 three)

; => (+ 2 2 three)