The specific syntax of Lisp dialects allows one to precisely define and distinguish basic constructs, add new syntactic elements, and even transform program code while it is running. This stems from the use of simple yet well-thought-out ways of organizing and representing source code.

Basic Constructs

Programs written in Lisp variants are characterized by simple syntactic rules. Rather than discussing them theoretically, we will begin with a practical example that we will refer back to in order to learn the basic mechanisms governing the translation of source code into a form understandable by a computer. By tracing what the compiler does, we will better understand the constructs of the language.

Here is our base example:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

Not particularly difficult. Is it?

Syntax

Lisp looks like oatmeal with toenail clippings mixed in.

– Larry Wall

Let us start with syntax. The first thing that catches the eye when we see programs written in Lisp dialects is the placement of nearly every compound construct within parentheses. In other programming languages, parentheses serve to group selected syntactic elements, e.g., arguments when calling or defining a function, sets of conditions, or operations on values. In Lisps, parentheses are the fundamental lexical element used to give shape to the entire program and to every expression.

In Lisp-family languages we construct expressions using the so-called Polish notation (PN), also known as prefix notation. It consists of placing the operator (function name) first, followed by the operands (call arguments). Parentheses are used to mark the beginnings and ends of expressions.

Prefix notation differs from the infix notation popular in many programming languages, but not enough to make it very difficult to recognize the individual parts of expressions. Our sample program can be expressed in Ruby as follows:

print "Hello, Lisp!"

print "Hello, Lisp!"

And in C in the following way:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("Hello, Lisp!");

return 0;

}

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("Hello, Lisp!");

return 0;

}

The differences between the discussed notations can be well illustrated with mathematical operations. Let us look at two simple computations:

2 + 2 * 3

2 + 2 * 3

And the notation conforming to Clojure syntax:

(+ 2 (* 2 3))

(+ 2 (* 2 3))

We can notice that in the second example the addition operator and its operands are enclosed in parentheses, and the name of the operation is always in the first position. An advantage of this notation is that there is no need to remember operator precedence.

Furthermore, in Polish notation, to represent more complex constructs in which we need to express containment relations, we do not need additional grouping markers (such as, e.g., curly braces or indentation) or separators (e.g., semicolons). Syntactic processing of expressions in prefix notation is simpler and faster because, owing to the more clearly defined structure, it requires fewer rules.

Reader

Let us return to our program:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

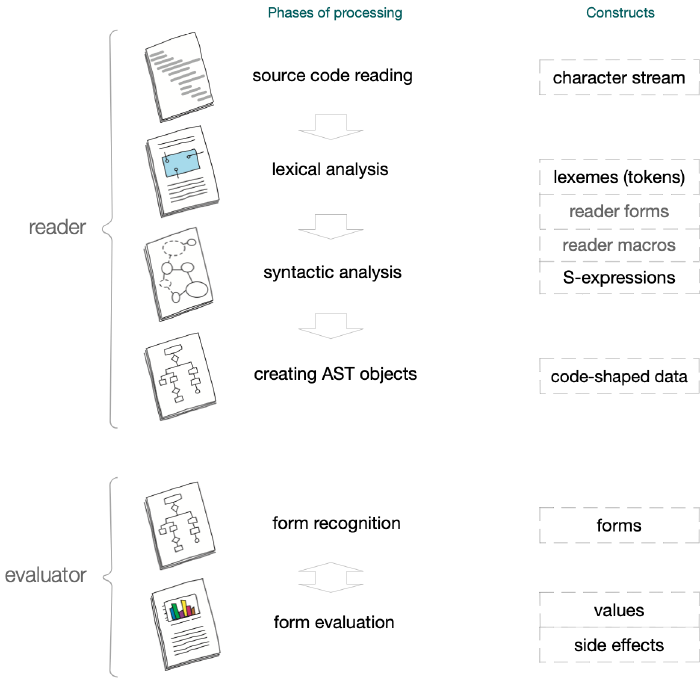

The first stage of transforming its text into executable form is reading it into memory. In Lisps, the component responsible for this is called the reader. Its task is to open a file located on disk or an input stream associated with the user’s terminal and to subject the text being read to processing, in which we can distinguish two main phases:

-

detecting known lexical constructs in the text;

-

extracting grammatically correct expressions from the detected constructs and representing them as internal, in-memory structures.

Lexical analysis

The first phase of reading program sources into memory is lexical analysis. It consists of:

-

cleaning the input of unnecessary symbols;

-

recognizing in the character stream sequences matching the lexical units defined in the language lexicon, in this context called tokens;

-

extracting from the text fragments that have syntactic significance (so-called lexemes), which are a kind of instances of the detected tokens.

The result of lexical analysis applied to our example will be a stream of lexemes – that is, extracted fragments of the program text that have syntactic significance:

| Lexeme | Token name |

|---|---|

( |

list literal (opening) |

print |

symbol |

"Hello, Lisp!" |

string literal |

) |

list literal (closing) |

During the described process (called tokenization) the extracted lexemes may optionally be annotated with information about their corresponding tokens, so that this task does not need to be repeated during subsequent analyses.

Because of the specific syntax of Clojure (similarly to other Lisp dialects), lexical analysis is greatly simplified and often amounts to passing control to the parser as soon as a lexeme is found.

Syntactic analysis

The second phase of processing source code into an in-memory form is syntactic analysis, also called parsing. It encompasses:

-

recognizing syntactic constructs in the stream of lexemes by comparing their kinds and positions against the grammatical rules of the language;

-

extracting expressions – that is, grammatical constructs whose values can be computed in later compilation stages;

-

producing in-memory representations of the found expressions using appropriate data structures;

-

placing the resulting objects in the abstract syntax tree (AST).

The result of syntactic analysis is the representation of the program’s source code in memory accessible to the compiler.

Reader forms

Reader forms is a term used in Clojure to describe lexical units used to build grammatically correct syntactic constructs.

The table below lists the basic reader forms. The first column contains the token name, the second column shows example lexemes, and the last column indicates the data type of the in-memory object that will represent the lexemes in the abstract syntax tree, provided grammatical requirements are met.

| Token name | Example lexemes | Data type |

|---|---|---|

| symbol | onespace/two |

Symbol |

| nil literal | nil |

nil |

| keyword literal | :one::two:space/x::space/y |

Keyword |

| string literal | "one two" |

java.lang.String |

| list literal | (1 2 3) |

PersistentList |

| vector literal | [1 2 3] |

PersistentVector |

| map literal | {:a 1 :b 2}::{:a 1 :b2}:space{:a 1 :b 2} |

PersistentArrayMapPersistentHashMap |

| boolean literal | true, false |

java.lang.Boolean |

| integer literal | 10xff0172r1101 |

java.lang.Long |

| rational literal | 1/2 |

Ratio |

| big number literal | 1.2M1N |

java.math.BigDecimalBigint |

| float literal | -2.7e-4 |

java.lang.Double |

Reader macros

In Clojure, some syntactic constructs are implemented as so-called reader macros. These are also subroutines responsible for processing lexical units, but implemented somewhat differently. Instead of being hardcoded into the reader’s rule set, they reside in a special read table, where specific tokens are assigned to the subroutines responsible for their analysis.

In Clojure, the programmer cannot modify the read table, and there are no indications that such a capability is planned for the future. The motivation is to maintain a unified syntax across projects of diverse origin. However, we can use so-called tagged literals, which resemble reader macros, although they are subject to certain syntactic constraints.

The following table presents reader macros:

| Token name | Example lexemes | Data type |

|---|---|---|

| quoting (quote) | 'one'(one two) |

varies |

| syntax quoting (syntax-quote) |

`one`(two three) |

varies |

| syntax unquoting (syntax unquote) |

~quote |

varies |

| syntax unquoting with splicing (syntax unquote-splicing) |

~@(list 1 2) |

varies |

| metadata map (metadata map) |

^{:doc "Description"} |

PersistentArrayMapPersistentHashMap |

| metadata key (metadata key) |

^:dynamic true |

PersistentArrayMapPersistentHashMap |

| metadata tag (metadata tag) |

^Integer x |

PersistentArrayMapPersistentHashMap |

| comment (comment) |

; comment |

none |

| character literal (character literal) |

\a, \b, \c, \newline |

java.lang.Character |

| dereference expression (dereference expression) |

@x |

java.lang.Class (with IFn) |

| Java member-access operator (Java member-access operator) |

(. " a " trim)(.trim " a ") |

varies |

| Java member-access operators (Java member-access operators) |

(.. "a" trim length) |

varies |

| dispatch macro (dispatch macro) | #… |

varies |

The last entry in the table is the so-called dispatch macro. This is a general term

for a subgroup of reader macros whose tokens all begin with the hash symbol (#).

When the reader encounters this character, it passes control over further analysis of

the construct to a separate macro table. Below is a list of tokens handled using the

dispatch macro:

| Token name | Example lexemes | Data type |

|---|---|---|

| Var quoting (var-quote) |

#'x |

Var |

| set literal (set literal) |

#{1 2 3} |

PersistentHashSet |

| regular expression (regular expression) |

#"one.tw[oO]" |

java.util.regex.Pattern |

| anonymous function literal (anonymous function literal) |

#(pr) |

java.lang.Class (with IFn) |

| anonymous function argument (anonymous function argument) |

#(pr %)#(pr %1 %2) |

PersistentTreeMap |

| ignore next form (ignore next form) |

#_ one two |

none |

| Java constructor call (Java constructor call) |

#name.type[:x]#name.record{:x 1} |

varies |

| reader conditional (reader conditional) |

$?(:clj "Clojure":cljs "ClojureScript") |

varies |

| tagged literal (tagged literal) |

#symbol argument |

varies |

inst tagged literal( inst tagged literal) |

#inst "2018-11-12" |

java.util.Date |

UUID tagged literal( UUID tagged literal) |

#uuid "88b05082-392d-4e0a-89c9-cf62ec375c43" |

java.util.UUID |

Note that some lexical units will not be represented by objects of a predetermined data type (marked “varies” in the type column). For example, quoting itself is not associated with producing a particular structure, but influences how a given construct is further parsed. We will also find tokens that do not cause any value to be generated (“none” in the type column), because they selectively exclude certain elements of the program text from the syntactic analysis process.

Also noteworthy is the type java.lang.Class with the annotation “with IFn”. This

notation indicates that in Clojure, function objects are expressed by anonymous Java

classes equipped with the IFn interface. This is related to the characteristics of

functions in Java – they do not have properties that would allow using them directly.

S-expressions

At the grammatical level, every element of source code in Lisp is a symbolically written expression. The textual representations of expressions – those we see in an editor – are called symbolic expressions, abbreviated as S-expressions (sexprs, sexps).

The structure of S-expressions somewhat resembles XML or JSON – that is, we are dealing with a notation that allows expressing nested and ordered sets of values, though in a somewhat simpler way than the aforementioned formats.

An S-expression in Lisp can be defined as a kind of notation in which:

- every element is an expression:

- non-compound (called an atom) or

- composed of S-expressions enclosed in parentheses and separated by a separator.

print ; atomic S-expression (not a list of S-expressions)

"Hello, Lisp!" ; atomic S-expression (not a list of S-expressions)

(print "Hello, Lisp!") ; list S-expression

() ; both list and atomic S-expression

(print (+ 2 2)) ; S-expression composed of nested S-expressions

print ; atomic S-expression (not a list of S-expressions)

"Hello, Lisp!" ; atomic S-expression (not a list of S-expressions)

(print "Hello, Lisp!") ; list S-expression

() ; both list and atomic S-expression

(print (+ 2 2)) ; S-expression composed of nested S-expressions

An S-expression in Clojure will be defined in a somewhat richer way, because we have additional collection literals there. It will be a kind of notation in which:

- every element is an expression:

- non-compound (called an atom) or

- composed of separated S-expressions:

- in pairs, enclosed in curly braces –

{...}; - individually, enclosed in:

- round parentheses –

(...); - curly braces with a hash symbol –

#{...}; - square brackets –

[...].

- round parentheses –

- in pairs, enclosed in curly braces –

In the case of expressions in curly braces, the first elements of pairs must be unique values within the entire expression, and in the case of expressions in curly braces preceded by a hash symbol, each value must be unique. This check is performed already during syntactic analysis, and when a given element requires prior computation, during evaluation.

:one ; atomic S-expression

1 ; atomic S-expression

print ; atomic S-expression

"Hello, Lisp!" ; atomic S-expression

(print "Hello, Lisp!") ; list S-expression

[1 2 3] ; vector S-expression

#{1 2 3} ; set S-expression

{:one 1 :two 2 :three 3} ; map S-expression

(str [1 2 3]) ; list and vector S-expressions

:one ; atomic S-expression

1 ; atomic S-expression

print ; atomic S-expression

"Hello, Lisp!" ; atomic S-expression

(print "Hello, Lisp!") ; list S-expression

[1 2 3] ; vector S-expression

#{1 2 3} ; set S-expression

{:one 1 :two 2 :three 3} ; map S-expression

(str [1 2 3]) ; list and vector S-expressions

The recursive definition of an S-expression may seem difficult to understand, so we will aid ourselves with our one-line program and perform a manual categorization of the elements present in it.

In the notation (print "Hello, Lisp!"):

(...)is an S-expression, because it is a symbolically written list of S-expressions;printis an S-expression, because it is an atom;"Hello, Lisp!"is an S-expression, because it is an atom.

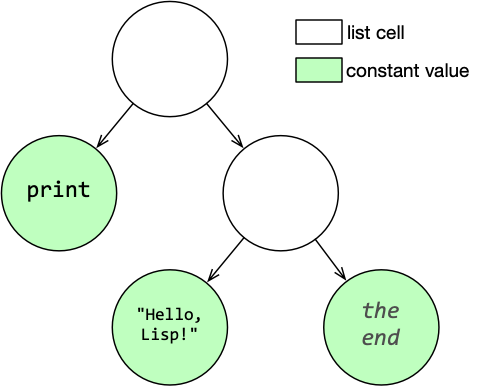

Graphically, this set can be presented as follows:

Unlike other Lisps, compound S-expressions in Clojure are built not only from lists marked by round parentheses, but also using additional markers that correspond to certain kinds of collections. Depending on the notation used, a data structure representing the appropriate kind of S-expression will be created in memory:

| Notation | Literal | S-expression | Structure | Data type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

(a...z) |

list | list | list | PersistentList |

[a...z] |

vector | vector | vector | PersistentVector |

{a b ... x y} |

map | map | map | PersistentArrayMapPersistentHashMap |

#{a...z} |

set | set | set | PersistentHashSet |

Atoms

When discussing symbolic expressions, we mentioned a specific class of them called atoms. An atom is an element of Lisp syntax that is not compound (is not: a list, a set, a vector, or a map). The exceptions are the empty list, the empty set, the empty vector, and the empty map, which are both compound expressions and atoms.

However, one more important condition must be added to the above definition, a condition that determines whether a symbolic notation can be considered a Lisp atom. Let us recall our program:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

In the previous examples, we could see that print and Hello, Lisp! are atoms, but

would any arbitrary set of characters that is not a pair of parentheses with content

qualify? No. An atom must be a valid syntactic construct on the basis of which the

reader will be able to decide what object to place in the AST. There is a certain

rigor here. In this particular case, the text print will be stored as a symbol, and

Hello, Lisp! as a string, because they satisfy the syntactic requirements for

representing specific data structures.

Admittedly, the syntactic rules are liberal enough that most randomly typed words or even single characters will be recognized as symbols (and thus atoms), but placing a parenthesis in a symbolic label or starting it with a digit would be serious violations, and the reader would stop cooperating with us.

It is worth noting that the concept of an atom as a class of syntactic expressions is not widely used among Clojure programmers. This is probably because in Clojure there exists a reference data type called Atom which helps perform concurrent data operations.

List S-expressions

The most commonly encountered class of S-expressions are list S-expressions. It is thanks to them that programs written in Lisp dialects consist of a large number of parentheses.

A list S-expression in Clojure should be a list of elements (other S-expressions) separated by spaces, commas, or both. The beginning and end of a list S-expression should be marked by an opening and closing round parenthesis.

List expressions with symbols placed in their first positions serve to invoke subroutines (functions, macros, or special constructs) identified by them. The remaining elements of the list then express arguments passed to the invocation. In the case of functions, argument values will be computed before being applied.

If no elements are provided, a list S-expression will produce an empty list.

1;; calling the + function

2

3(+ 1 2 3)

4;=> 6

5

6;; calling the defn macro

7;; used to define a named function

8

9(defn greet [] "Hello!")

10;=> #'user/greet

11

12;; calling the defined greet function

13

14(greet)

15;=> "Hello!"

16

17;; special form def

18;; used to define a global variable

19

20(def x 2)

21;=> #'user/x

22

23;; doubling the value of the global variable

24;; identified by the symbol x

25

26(+ x x)

27;=> 4

28

29;; empty list

30

31()

32;=> ()

;; calling the + function

(+ 1 2 3)

;=> 6

;; calling the defn macro

;; used to define a named function

(defn greet [] "Hello!")

;=> #'user/greet

;; calling the defined greet function

(greet)

;=> "Hello!"

;; special form def

;; used to define a global variable

(def x 2)

;=> #'user/x

;; doubling the value of the global variable

;; identified by the symbol x

(+ x x)

;=> 4

;; empty list

()

;=> ()

Older Lisp dialects supported a somewhat different form of list S-expressions. Inside

a pair of parentheses one did not place a list of all elements, but only one cell of

the list, divided into a left and right value separated by a dot, with the end of the

list marked by the symbol nil, e.g.:

(+ . (1 . (2 . nil)))

(+ . (1 . (2 . nil)))

In Clojure, this kind of notation is not supported, although there are data structures that allow performing operations on individual cells and creating so-called sequences.

Vector S-expressions

Vector literals create so-called vector S-expressions, but unlike list expressions, elements placed in their first positions have no special significance. The result of using a vector S-expression in its basic form will be a data structure called a vector, and each of its elements will become a component of it after its value has been computed.

Using vector S-expressions we can:

-

create the aforementioned vectors and use them for application logic,

-

specify argument lists of defined functions and macros,

-

express bindings of symbols to values in appropriate special constructs (including

letandbinding), -

perform so-called positional destructuring of compound structures with a sequential access interface.

;; literal vector

[1 2 3 4]

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; literal vector

[(+ 1 1) 2 3 4]

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; bindings vector in a let form

;; creates a lexical binding of symbol a to value 1

(let [a 1] a)

;=> 1

;; vector binding form in a let form (destructuring)

;; inside the bindings vector of the let form

;; binds each symbol from the S-expression [a b]

;; to an initializing value from the S-expression [1 2]

;; according to position

(let [[a b] [1 2]]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; argument list in a named function definition

(defn add

[a b]

(+ a b))

(add 2 2)

;=> 4

;; empty vector

[]

;=> []

;; literal vector

[1 2 3 4]

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; literal vector

[(+ 1 1) 2 3 4]

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; bindings vector in a let form

;; creates a lexical binding of symbol a to value 1

(let [a 1] a)

;=> 1

;; vector binding form in a let form (destructuring)

;; inside the bindings vector of the let form

;; binds each symbol from the S-expression [a b]

;; to an initializing value from the S-expression [1 2]

;; according to position

(let [[a b] [1 2]]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; argument list in a named function definition

(defn add

[a b]

(+ a b))

(add 2 2)

;=> 4

;; empty vector

[]

;=> []

Map S-expressions

Using the map literal we can construct map S-expressions. In their basic form they allow expressing an associative data structure called a map, which consists of indexed key–value pairs. Values should be separated by spaces, commas, or both. The first element of each pair is called the key, and the second the value.

Using map S-expressions we can:

-

create the aforementioned maps and use them for application logic,

-

specify named argument lists of defined functions and macros,

-

construct so-called metadata maps that allow enriching certain constructs with metadata that can describe them or control their properties;

-

perform associative destructuring of compound structures with an associative access interface.

;; literal map

{"a" 1 "b" 2}

;=> {"a" 1 "b" 2}

;; map expressing named arguments

;; of a defined function

;; keys a and b must be strings

(defn add [& {:strs [a b]}]

(+ a b))

;; calling a function with named arguments

(add "b" 1, "a" 3)

;=> 4

;; metadata map of a defined function

;; with a documentation string (key :doc)

(defn add

{:doc "This function adds two numbers."}

[a b]

(+ a b))

;=> #'user/add

;; calling the documentation string for add

(doc add)

;=>> -------------------------

;=>> user/add

;=>> ([a b])

;=>> This function adds two numbers.

;=> nil

;; map binding form in a let form (destructuring)

;; inside the bindings vector of the let form

;; binds symbols a and b

;; to values from a map indexed by "a" and "b"

(let [{:strs [a b]} {"b" 1 "a" 3}]

(+ a b))

;=> 4

;; empty map

{}

;=> {}

;; literal map

{"a" 1 "b" 2}

;=> {"a" 1 "b" 2}

;; map expressing named arguments

;; of a defined function

;; keys a and b must be strings

(defn add [& {:strs [a b]}]

(+ a b))

;; calling a function with named arguments

(add "b" 1, "a" 3)

;=> 4

;; metadata map of a defined function

;; with a documentation string (key :doc)

(defn add

{:doc "This function adds two numbers."}

[a b]

(+ a b))

;=> #'user/add

;; calling the documentation string for add

(doc add)

;=>> -------------------------

;=>> user/add

;=>> ([a b])

;=>> This function adds two numbers.

;=> nil

;; map binding form in a let form (destructuring)

;; inside the bindings vector of the let form

;; binds symbols a and b

;; to values from a map indexed by "a" and "b"

(let [{:strs [a b]} {"b" 1 "a" 3}]

(+ a b))

;=> 4

;; empty map

{}

;=> {}

Set S-expressions

The set literal enables writing set S-expressions. Thanks to them, one can express sets in a clear and straightforward way – that is, structures in which each element appears only once.

The set literal consists of curly braces preceded by a hash symbol, inside which unique-within-the-set values are placed. Elements of a set S-expression should be separated by a space, a comma, or both.

If an element of a set expression is not a constant value, it will be computed before the object representing the set is created.

#{1 2 3 4}

;=> #{1 2 3 4}

#{1 (+ 1 1) 3 4}

;=> #{1 2 3 4}

;; empty set

#{}

;=> #{}

#{1 2 3 4}

;=> #{1 2 3 4}

#{1 (+ 1 1) 3 4}

;=> #{1 2 3 4}

;; empty set

#{}

;=> #{}

Abstract syntax tree

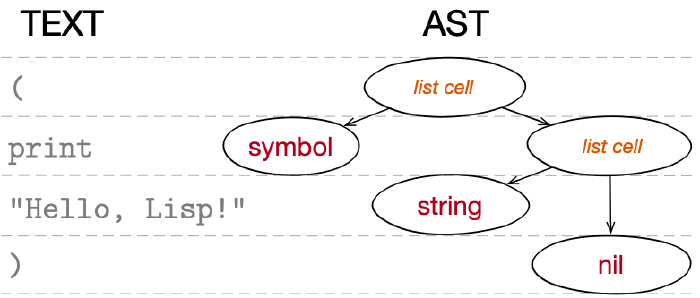

We know that the result of syntactic analysis is a form of source code in the abstract syntax tree. Let us see what it will look like after reading our program:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

The opening parenthesis at the beginning will cause the reader’s mechanisms to treat the lexical construct as a list literal. Taking the content into account, it will form a grammatical construct: a list S-expression. During the parsing phase it will be transformed into a list object – that is, a structure used to store an ordered set of data. These data will be the representations of the two atomic S-expressions placed within the parentheses:

The syntax tree is not an element specific to Lisps. Compilers and interpreters of other programming languages also use it. However, in their case the AST is partially or entirely inaccessible to the programmer and built using internal data structures that are not supported by the language. Operating on the syntax tree from within the program is either impossible or limited to using special macro mini-languages. In Lisps, things are different, as we will learn later.

Returning to our program… The first element of the list S-expression is the atom

print. It will be recognized as another known syntactic element: a symbol. The

rules of the language state that it must be a word composed of alphanumeric characters

that does not begin with a digit or with a special character indicating data of

a different kind. In the in-memory list structure, an object of type

Symbol will be placed at the first position. This data type resembles

keywords or text labels known from other languages – it will be discussed more broadly

in a later section.

The last component of the symbolic expression we entered is the string literal

Hello, Lisp!, which can be detected by the quotation marks surrounding the text. It

too is an atom and will be treated as a representation of a string, which will be

placed at the end of the list residing in the syntax tree.

To summarize, in the AST the following will be created:

- a data structure (list) consisting of:

- a datum of type symbol,

- a datum of type string.

Let us notice that the graphical representation of source code in the abstract syntax tree and the earlier-shown way of organizing S-expressions are similar to each other. Coincidence?

Homoiconicity

In Lisps, the in-memory AST objects are represented using the same data structures that we can use in programs. Moreover, their arrangement in the syntax tree is the same as the layout of S-expressions in the textual representation. In other words: the abstract syntax tree and the program text are isomorphic. If necessary, we can read the AST and obtain readable source code in the form of symbolic expressions.

The trait described here is called homoiconicity and opens the possibility of transforming S-expressions reflected in the AST using the system of syntactic macros, to which a separate chapter will be devoted.

Semantics

The next important stage of transforming a program into executable form is semantic analysis – that is, the process of recognizing the meaning-bearing constructs of the language. In Lisp dialects, this is one of the first tasks of the component called the evaluator. It consists of reading the objects of the abstract syntax tree representing expressions, checking whether they are semantically correct, and computing the value of each one by running the appropriate subroutines. In the case of Clojure, part of this process will be carried out during compilation, and part at program runtime.

Let us recall our example once more:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

After reading the source code into memory, data representing it were placed in the AST, and during program execution, each datum will be evaluated in order to ultimately obtain the value of the outermost S-expression.

In the given example, the first element of the list is the symbol print, which

identifies a built-in Clojure function used to display text on the screen. By

examining the current namespace, the compiler will find the appropriate

mapping of the symbol to a function object and determine that it is

dealing with a construct that is a function call. It will also identify the

subroutine that needs to be invoked to perform the operation.

Functions can accept arguments, and the given symbolic expression also contains (apart

from the operation name) an argument intended for its call. Because in Lisps we are

dealing with pass-by-value, the process of evaluating the string Hello, Lisp! will

be performed first. A string is a constant value, so no further computation will be

required, and it is this value that will be passed to the call.

Running the print function subroutine will produce the intended side effect of

displaying the following on screen:

Hello, Lisp!

Additionally, the function will return a value that, depending on how the program was launched, will be displayed (in the case of an interactive console) or remain unhandled (in other cases).

Forms

The abstract syntax tree in Lisps is data organized as nested lists. Each such datum is a Lisp form, called simply a form – that is, an in-memory representation of a syntactically valid S-expression intended for evaluation.

The evaluator, analyzing AST elements, attempts to compute their values, paying attention to data types and the contexts in which they appear. Several main decision paths of the evaluating subroutine are possible, corresponding to different kinds of forms encountered.

By examining only the data structures in the AST or the S-expressions in the source

code text, we cannot precisely determine what specific form we will be dealing

with. This can only be established during evaluation. For example, the symbol x

placed at the first position of the list S-expression (x 1) may, after evaluation,

turn into a function object – and then it will be a function-call form for x – but

it may also turn out to be, say, a map, and then it will be a map lookup form where

the value 1 is treated as a key.

Before we proceed to discussing the main kinds of forms, let us name those that will be recognized in our program:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

(...)– compound form,print– symbol form,"Hello, Lisp!"– normal form,(print "Hello, Lisp!")– function-call form:- after detecting that

printis bound to a function; - after detecting the function’s argument form;

- after computing the argument to a normal form.

- after detecting that

Constant and normal forms

A source code expression representing a constant value that does not require computation will be recognized by the evaluator as a so-called constant form and passed unchanged to the calling, parent construct.

The most direct kind of constant form is the so-called normal form – a source code datum that by its nature does not require evaluation, because it is already represented in the syntax tree by its own value. Examples include numeric literals and string literals.

"Hello, Lisp!" ; string

\a ; character

() ; empty list

123 ; integer

'lalala ; quoted symbol

"Hello, Lisp!" ; string

\a ; character

() ; empty list

123 ; integer

'lalala ; quoted symbol

An interesting kind of constant form is the result of applying the quote form –

a special syntactic form that allows disabling evaluation of the S-expressions passed

to it and treating the source code data as constant structures. The quote construct

and the quoting mechanism will be discussed in more detail further on.

Symbol forms

A symbol will be treated by the evaluator as a symbol form, and it will attempt to find the object bound to it, which – depending on the context – may be assigned to that symbol’s name in various places, e.g., in lexical bindings or namespaces (and global variables). The obtained value will be substituted in place of the symbol’s occurrence.

print

+

print

+

See also:

- “Symbol forms”, chapter IV.

Compound forms

When the evaluator encounters a non-empty collection, it will recognize it as a so-called compound form.

In the case of a map form, a vector form, or a set form, each element will be evaluated, and a collection will be returned in which every element has been computed to a constant form.

[1 2 3] ; vector form

#{1 2 3} ; set form

{"a" 1 "b" 2} ; map form

'(1 2 3) ; list form (literal list)

[1 2 3] ; vector form

#{1 2 3} ; set form

{"a" 1 "b" 2} ; map form

'(1 2 3) ; list form (literal list)

In the case of a list or a sequence of Cons objects, the value of

the first element will be computed, and a decision will be made regarding the further

course of action depending on the detected form.

Lookup forms

If the first element of a list form being evaluated is a vector, a set, or a map, then a vector lookup form, a set lookup form, or a map lookup form will be recognized, respectively. The value of the next element in the list will be passed as an argument to the subroutine responsible for finding elements by given indices. If there are more arguments, an error will be generated.

([1 2 3] 0) ;=> 1

(#{1 2 3} 2) ;=> 2

({"a" 1 "b" 2} "b") ;=> 2

([1 2 3] 0) ;=> 1

(#{1 2 3} 2) ;=> 2

({"a" 1 "b" 2} "b") ;=> 2

If the first element of a list form being evaluated is a keyword or a literal symbol, then a keyword lookup form or a symbol lookup form will be recognized, and the value of the next element in the list will be passed as an argument to a subroutine that uses the given keyword or symbol as an index to find the value. If there are more arguments, an error will be generated.

(:a {:a 1 :b 2}) ;=> 1

(:a #{:a :b :c}) ;=> :a

('a {'a 1 'b 2 :c 3}) ;=> 1

(:a {:a 1 :b 2}) ;=> 1

(:a #{:a :b :c}) ;=> :a

('a {'a 1 'b 2 :c 3}) ;=> 1

Function-call forms

If the first element of a list form being evaluated is a function object, the expression will be treated as a function-call form, and the computed values of the remaining elements of the list will be passed as arguments to the subroutine associated with that object. This also applies to Java methods.

(print "Hello, Lisp!") ;=> nil =>> Hello, Lisp!

(+ 2 2) ;=> 4

(.toLowerCase "A") ;=> a

(print "Hello, Lisp!") ;=> nil =>> Hello, Lisp!

(+ 2 2) ;=> 4

(.toLowerCase "A") ;=> a

Special forms

If the first element of a list form being evaluated is one of the so-called syntax forms, the built-in handler subroutine for the associated special form will be launched, and the remaining elements of the list will become its arguments (after their prior evaluation or without evaluation).

(def x 1) ; defining a global variable

(fn [x] (inc x)) ; creating a function

(def f (fn [x] (inc x))) ; defining a named function

(let [a 1] a) ; creating lexical bindings

(quote (1 2 3)) ; quoting

(. System (getProperty "user.home")) ; accessing Java classes

(def x 1) ; defining a global variable

(fn [x] (inc x)) ; creating a function

(def f (fn [x] (inc x))) ; defining a named function

(let [a 1] a) ; creating lexical bindings

(quote (1 2 3)) ; quoting

(. System (getProperty "user.home")) ; accessing Java classes

Special forms are – as the name itself indicates – forms characterized by special evaluation rules. In essence, a special form is a kind of function built into the language, whose – similarly to macros – arguments are not all immediately evaluated.

Thanks to special forms we can, for example, define global variables or functions, and also create bindings of symbols to values in certain areas of a program.

Recursive evaluation of forms

When a datum obtained in the course of the evaluator’s work turns out not to be

a constant value, but another form requiring evaluation, it will be recursively

computed until a constant form is obtained. For example, a symbol form may emit

a Var reference object, which in turn will point to the subroutine of the

function being called.

Invalid forms

If it turns out that a given AST element is not a valid form – that is, one whose value cannot be computed (reduced to a constant form) – an error message will be generated and the program will terminate abnormally.

1(1 2 3) ; the number 1 cannot be cast to a function type

2(()) ; an empty list cannot be cast to a function type

3(+ /) ; the function / cannot be cast to an integer type

4(no_such) ; no construct identified by the symbol no_such

5no_such ; no construct identified by the symbol no_such

(1 2 3) ; the number 1 cannot be cast to a function type

(()) ; an empty list cannot be cast to a function type

(+ /) ; the function / cannot be cast to an integer type

(no_such) ; no construct identified by the symbol no_such

no_such ; no construct identified by the symbol no_such

The names of some forms are conventional – that is, they are based on the assumption that certain S-expressions can be computed to data of specific types. For example, the notation:

(add 1 2 3)

(add 1 2 3)

we will conventionally call a function-call form, even though in reality we are not

certain whether the symbol form add will be recognized in the namespace as a global

variable, and whether the reference object found there will contain a reference to

a function.

Binding forms

A binding form is a construct in which a value is assigned to a symbolic identifier in order to create a binding. At the syntactic level, these forms will contain unquoted symbols, but they will not be treated as symbol forms whose values need to be resolved; rather, they serve as expressions that assign in-memory objects to symbolic names.

We will recognize a binding form in expressions representing certain special forms, where we will encounter:

-

a pair composed of an unquoted symbol and another form (representing the value that, once computed, is to be assigned);

-

an unquoted symbol appearing on its own, e.g., in a function’s parameter vector, where the value will be dynamically assigned when arguments are passed during the function’s invocation.

Symbol binding forms are components of certain compound forms and [special forms][formy specjalne]. We will find them, for example:

-

in the argument specifying a name:

-

in the bindings vector:

- of the special form

letand similar, - of the special form

loopand similar, - of the macro

with-local-vars, - of the macro

binding;

- of the special form

-

in the argument specifying a name and/or the parameter vector:

Additionally, binding forms may also appear in so-called structural bindings – that is, abstract bindings in which compound data structures are destructured and symbols are assigned values at specified positions or identified by given keys. We will then encounter a vector binding form or a map binding form, in which instead of a single unquoted symbol on the left side, a vector or map S-expression appears.

Some other constructs that use binding forms can also be intuitively referred to as

binding forms. These are expressions whose primary purpose is to create

bindings. For example, the special form let will also be called

a let binding form, even though in reality it uses potentially many basic binding

forms grouped in a bindings vector.

(def x 5) ; symbol x in a binding form

(fn [x] nil) ; symbol x in a binding form

(let [x 2]) ; symbol x in a binding form

(defn some-fn ; symbol some-fn in a binding form (function name)

[x] ; symbol x in a binding form (parameter name)

nil)

(def x 5) ; symbol x in a binding form

(fn [x] nil) ; symbol x in a binding form

(let [x 2]) ; symbol x in a binding form

(defn some-fn ; symbol some-fn in a binding form (function name)

[x] ; symbol x in a binding form (parameter name)

nil)

It is worth noting that in the case of function arguments, the symbols identifying their parameters will be dynamically assigned to the values of arguments passed at the moments of function invocation.

See also:

- “Bindings”;

- “Symbol binding forms”, chapter IV;

- “Bindings and namespaces”, chapter VI.

Quoting

An important special construct in Clojure and other Lisps is the special form quote,

which allows disabling evaluation of the S-expression given as its argument. A

syntactic construct written this way will be read and syntactically analyzed, but the

phase of semantic analysis will be skipped for it. Appropriate data structures will be

placed in the AST, but they will be marked as constant forms. Instead of computing

their values, the evaluator will simply return the data structures found in the syntax

tree.

In Lisp dialects, using the quote form allows creating literal variants of

structures that in their unquoted forms would be used to represent program source code

and/or would be evaluated.

quote form

1(quote one) ; literal symbol

2(quote (1 2 3)) ; literal list

3(quote [a b]) ; literal vector

4(quote {a 1 b 2}) ; literal map

5(quote #{1 2 3}) ; literal set

(quote one) ; literal symbol

(quote (1 2 3)) ; literal list

(quote [a b]) ; literal vector

(quote {a 1 b 2}) ; literal map

(quote #{1 2 3}) ; literal set

The above can also be written using syntactic sugar:

'one

'(1 2 3)

'[a b]

'{a 1 b 2}

'#{a b}

The same data structures could be produced without using quoting, by using the appropriate built-in functions of the language:

1(symbol "one") ; symbol

2(list 1 2 3) ; list

3(vector (symbol "a") (symbol "b")) ; vector

4(hash-map (symbol "a") 1 (symbol "b" 2}) ; map

5(hash-set 1 2 3) ; set

(symbol "one") ; symbol

(list 1 2 3) ; list

(vector (symbol "a") (symbol "b")) ; vector

(hash-map (symbol "a") 1 (symbol "b" 2}) ; map

(hash-set 1 2 3) ; set

Quoting is recursive – that is, every S-expression nested within a quoted one will also be quoted.

1(quote (a b c)) ; list with literal symbols

2(quote (+ 2 (* 2 3))) ; list with literal symbols and numbers

3(quote [one 2 3]) ; vector with a literal symbol and numbers

4(quote {a 1 b 2}) ; map with literal symbols and numbers

5(quote #{a b c}) ; set with literal symbols

(quote (a b c)) ; list with literal symbols

(quote (+ 2 (* 2 3))) ; list with literal symbols and numbers

(quote [one 2 3]) ; vector with a literal symbol and numbers

(quote {a 1 b 2}) ; map with literal symbols and numbers

(quote #{a b c}) ; set with literal symbols

It is worth noting that the terms “literal map”, “literal set”, and “literal vector” may in certain contexts be considered overly zealous labels. Each element of symbolically expressed maps, sets, or vectors will be eagerly evaluated by the evaluator, and their evaluation ends there. They remain the same data structures and do not carry the same syntactic weight as lists.

Augmenting the names of the above-mentioned structures with the qualifier “literal” will make sense when we want to emphasize that the contents of their elements will not be computed. An example would be a situation in which the elements of a vector S-expression are symbols pointing to certain values. When we quote such a construct, the values of elements will not be computed during vector evaluation. If we want to emphasize this fact, we can call the vector literal.

[1 2 3] ; vector form (colloq. vector, rarely: literal vector)

[1 2 (inc 2)] ; vector form (colloq. vector)

'[1 2 (inc 2)] ; literal vector (colloq. vector)

'[1 2] ; literal vector

[1 2 3] ; vector form (colloq. vector, rarely: literal vector)

[1 2 (inc 2)] ; vector form (colloq. vector)

'[1 2 (inc 2)] ; literal vector (colloq. vector)

'[1 2] ; literal vector

The most sensible approach seems to be to describe maps, vectors, and sets as literal when they are expressed in a quoted form. In the case of unquoted forms (subject to evaluation), colloquial terms can be used.

Let us also try quoting applied to our template program:

'(print "Hello, Lisp!")

'(print "Hello, Lisp!")

The result of evaluating the above expression is a value which is a list containing a symbol and a string – that is, our original program, expressible as the text:

(print "Hello, Lisp!")

It is worth noting that when a constant form is quoted, its value after evaluation is

still its own previous, constant value, as we can observe with the string

Hello, Lisp!.

Identifiers

Identifiers are constructs that allow us to name identities (e.g., individual values or compound data structures placed in memory) so that we can later refer to them.

In Clojure there are identification constructs (symbols, discussed below) that carry special syntactic meaning and whose named objects are resolved automatically. There are also constructs (e.g., keywords) that serve to identify utility data, but their use is not mandatory.

Symbols

A symbol in Clojure is a data type whose instances serve to identify structures placed in memory. Thanks to symbols (and the appropriate handling of them by the reader mechanisms) we can give names to functions and their arguments, to the results of computations, and to other objects, and subsequently refer to them using human-readable identifiers.

In Clojure, symbol forms can be expressed in program text without any additional markers. A symbol’s name is at the same time its own identifier, although the symbol object placed in the AST will be subject to further evaluation by the evaluator (it will not be self-evaluating).

Syntactically speaking, every symbol has a name that must be a string beginning

with a non-digit character and may contain alphanumeric characters as well as:

*, +, !, -, _, and ?.

1func ; func is a symbol form

2(func 1 2 3) ; func is a symbol form in a function-call form

3(fn [x y] x) ; symbols x and y are parameters of an anonymous function

4 ; [x y] contains two symbol binding forms

5(.toLowerCase "A") ; toLowerCase is a Java class method

6

7; ChunkedSeq is an inner class of PersistentVector

8(new clojure.lang.PersistentVector$ChunkedSeq [1 2 3 4 5] 0 3)

func ; func is a symbol form

(func 1 2 3) ; func is a symbol form in a function-call form

(fn [x y] x) ; symbols x and y are parameters of an anonymous function

; [x y] contains two symbol binding forms

(.toLowerCase "A") ; toLowerCase is a Java class method

; ChunkedSeq is an inner class of PersistentVector

(new clojure.lang.PersistentVector$ChunkedSeq [1 2 3 4 5] 0 3)

In many Lisps a symbol is a reference type, meaning it independently identifies another object by storing a reference to its in-memory structure. In Clojure things are different – a symbol does not hold any reference, and the fact that we can use symbol forms to invoke functions or refer to constant values is owed to the appropriate treatment by the evaluator and the searching of additional structures (e.g., namespaces or lexical bindings areas).

The dot character (.) within a symbol’s textual name carries special

significance, as it allows building identifiers that refer to class names

of the host system, i.e., Java.

Namespaced symbols

A symbol may optionally contain an additional name specifying a so-called namespace – a special collection that serves to group identifiers in order to eliminate conflicts. More details about using this visibility-control mechanism can be found later in this episode.

The namespace name is a string subject to the same syntactic rules as the symbol

name, and is expressed by placing it before the symbol name and separating it

with a slash (/), for example:

1my/func ; symbol func with namespace my

2(my/func 1 2) ; symbol func with namespace my in a function-call form

my/func ; symbol func with namespace my

(my/func 1 2) ; symbol func with namespace my in a function-call form

In the symbol object itself we will find no reference to the namespace other than a textual one. Here too, no reference is stored. We can specify a nonexistent namespace and it will not be an error – not until the evaluator begins evaluating the notation.

Literal symbols

We encounter symbols primarily in the abstract syntax tree, where they will be symbol forms representing identifiers of other objects. Additionally, we can use literal symbols (constant forms) in application logic. In that case they will serve, for example, as simple enumerated types, representing constant values belonging to fixed sets:

1(list (symbol "little") (symbol "much") (symbol "most"))

2(list 'little 'much 'most)

3'(little much most)

(list (symbol "little") (symbol "much") (symbol "most"))

(list 'little 'much 'most)

'(little much most)

The three notations above are equivalent. The first constructs a literal list

whose elements are symbols created from strings using the built-in symbol

function; the second also produces a list, but uses quoting to express literal

symbols; the third makes use of recursive quoting of the entire list

S-expression.

Constant forms of symbols may also include a namespace designation:

(symbol "name" "space")

'name/space

In Lisps, literal symbols are sometimes used as indexing keys in associative structures (e.g., maps):

{ 'little 21, 'much 108, 'most 11 }

{ 'little 21, 'much 108, 'most 11 }

In Clojure, using symbols for this purpose is not recommended because they are not interned – two symbols with the same name will be represented by two different in-memory objects. In other words: in Clojure, symbol instances with the same names are not singletons.

If we used symbols to index large, frequently accessed structures, a great many temporary objects would be created, and the garbage collector would have to deal with them at the cost of valuable time. Another drawback is less efficient comparison (and hence searching), since symbol names would be compared rather than internal object identifiers.

See also:

- “Symbols”, chapter IV.

Keywords

A keyword (colloquially called a key) is a data type that –

similarly to symbols – serves to identify other objects, but in Clojure it

carries no special syntactic meaning and keywords do not automatically identify

other program constructs. Keywords are represented by objects of type

clojure.lang.Keyword.

Unlike symbols, keywords are interned. Two keywords with the same name will be represented in memory by the same object (their singleton).

Keywords work well as simple enumerated types or as indices in associative data structures (e.g., maps). As for the built-in mechanisms of the Clojure language, we will encounter keywords in certain macros and in constructs that express named arguments bindings of functions.

From the syntactic point of view, every keyword has a name that must be a string

beginning with a colon (:) and may contain alphanumeric characters as well

as: *, +, !, -, _, and ?. In practice a slightly richer character

set may be used (e.g., the dot is increasingly common for denoting internal

hierarchies in some libraries), but this may change in the future, so it is

worth using key names consistent with the language documentation.

Keywords are also functions. When we place a keyword in the first position of a list S-expression, a subprogram will be invoked that tries to look up an index in an associative or set collection given as an argument.

Like symbols, keywords may optionally include a namespace designation.

:a-key ; keyword

::a-key ; keyword with current namespace

:space/a-key ; keyword with namespace

::user/a-key ; keyword with namespace (existing)

(keyword "a-key") ; keyword from a string

(keyword "space" "a-key") ; same but with namespace specified

{:a 1 :b 2} ; map with keyword indices

(defn x [& {:keys [color]}] color) ; function with a named keyword argument

(x :color 123) ; calling function with keyword argument

(:a {:a 1 :b 2}) ; keyword as a function searching a map

(:a #{:a :b :c :d}) ; keyword as a function searching a set

:a-key ; keyword

::a-key ; keyword with current namespace

:space/a-key ; keyword with namespace

::user/a-key ; keyword with namespace (existing)

(keyword "a-key") ; keyword from a string

(keyword "space" "a-key") ; same but with namespace specified

{:a 1 :b 2} ; map with keyword indices

(defn x [& {:keys [color]}] color) ; function with a named keyword argument

(x :color 123) ; calling function with keyword argument

(:a {:a 1 :b 2}) ; keyword as a function searching a map

(:a #{:a :b :c :d}) ; keyword as a function searching a set

See also:

- “Keywords”, chapter IV.

Namespaces

In Clojure a construct called a namespace is used. In information technology this term denotes a mechanism for controlling the visibility of identifiers that allows their hierarchical grouping in order to avoid conflicts. Common examples of namespaces include file system directory structures, DNS records, and public IP addresses.

Namespaces in computer programming help separate sets of identifiers used in different components (e.g., programming libraries) or contexts, so that the exposed names (e.g., of modules, classes, variables, or functions) are unique. We can then use several libraries in a program that define functions with the same name. When referring to such a function, a so-called fully qualified name will be required – an identifier enriched with a namespace designation.

In Clojure, namespaces are implemented as globally visible maps, i.e.,

dictionaries storing key-value mappings. In their case the keys are

symbols, and the values are global variables or Java classes. The

data type used to represent namespace objects is clojure.lang.Namespace.

Since symbols placed in a program may optionally include a namespace

designation, it is possible to use them to refer to identifiers from different

namespaces. If a symbol does not contain a fully qualified name, then during its

evaluation it is assumed that it identifies a construct defined in the current

namespace, pointed to by the dynamic global variable

clojure.core/*ns*:

;; symbol select from namespace clojure.set

;; identifies a function

(clojure.set/select odd? #{1 2 3 4})

;=> #{1 3}

;; symbol + from namespace clojure.core

;; imported into the current namespace (user)

;; identifies a function

(+ 2 2)

;=> 4

;; symbol select from namespace clojure.set

;; identifies a function

(clojure.set/select odd? #{1 2 3 4})

;=> #{1 3}

;; symbol + from namespace clojure.core

;; imported into the current namespace (user)

;; identifies a function

(+ 2 2)

;=> 4

The first symbol in the above example has the name select and its namespace

is specified by the string clojure.set. Since this is a function-call form,

it will be treated as the identifier of a function whose subprogram needs to

be executed. To find the function object, the namespace clojure.set will be

searched and within it the key identified by the symbol select and the

global variable assigned to it. Inside the reference object,

a reference to the function subprogram will be found and invoked with the

arguments given as the subsequent elements of the list S-expression (odd? and

#{1 2 3 4}).

The second symbol in the example has no namespace specified. The evaluator will

therefore read the contents of the dynamic global variable *ns*, which by

default in the REPL console points to the namespace user. There it will find

the binding of the symbol + to a Var object, which refers to the

built-in addition function. The latter does not originally reside in the

namespace user but was imported into it along with other mappings from the

namespace clojure.core when the console was started.

See also:

- “Bindings and namespaces”, chapter VI.

Handling global state

When talking about Clojure, it is emphasized that there are no conventional variables and that data structures are immutable. Why, then, does the term “global variable” keep appearing?

Every programming language must handle changing global state – values that undergo change and are visible throughout the entire program under fixed names. Examples include: a character’s condition in a game, the arrangement of windows in a user interface, or the currently processed contents of a file being read.

To represent such data one might use conventional variables – fixed memory locations with given names whose contents are modified by appropriate subprograms (e.g., updating a score, reacting to user actions on interface elements, or reading data from a database). However, in such a model we cannot use multiple threads without applying additional isolation mechanisms. The memory slot of a variable representing an important parameter may be reorganized by one thread while another is still performing a critical operation with it. This means more work for the programmer, who instead of focusing on the application’s business logic must remember to safeguard the program against itself by introducing semaphores, locks, and similar constructs.

The opposite approach is to give up shared state entirely – a purely functional model in which no already-used memory area can ever be modified and the entire program consists of operations whose only input is their arguments and whose only output is their returned values. Handling graphical interfaces or tracking the activity of a logged-in user would in such a setup be cumbersome to express and inefficient. Imagine every user action triggering a cascade of function calls that each time recompute from scratch the values of all parameters constituting the program’s state at a given moment.

In Clojure we encounter a sensible compromise. Conventional variables do not exist, but thanks to appropriate reference types we are able to track and manage changing global state. This means that data mutations are permissible, but only as an exception and only using special constructs.

Reference objects in Clojure are equipped with concurrency-safe mechanisms for updating and reading the current values they point to. Instead of directly modifying the memory area containing data, an update to the reference takes place in such a way that the object begins pointing to a new value (placed at a different location). Values therefore remain constant and need not reside in variables, because the only element that undergoes mutation (overwriting of memory space) is the reference to them residing in reference objects.

The Var type

The most widely used reference type in Clojure is Var. It allows

creating references to data placed in memory and changing those references

within a given thread of execution. Additionally, a Var object may

optionally contain a so-called root binding, which is shared across all threads

and used when no thread-specific binding has been set.

By convention, Var objects in Clojure are interned in namespaces – there

is no commonly used special form or function that would allow creating them

without binding them to some symbolic identifier. There is, however, the

with-local-vars macro, which creates Var objects in lexical scope – they

must then be identified by given symbols visible within the expression passed

as an argument. We can read the values they point to using the deref function

or the dereference literal (the at sign placed before the symbol):

(with-local-vars [a 5] @a)

;=> 5

(with-local-vars [a 5] @a)

;=> 5

See also:

- “The Var type”, chapter VII.

Global variables

Objects of type Var (more precisely clojure.lang.Var) are used together with

symbols in Clojure to create global variables. Global variables serve to

identify infrequently changing identities, e.g., configuration values or

functions defined in the program.

It works as follows: a particular Var is assigned to a symbolic name by

placing an entry in one of the namespaces. This creates a global

binding of a symbol to the current value of the Var

object.

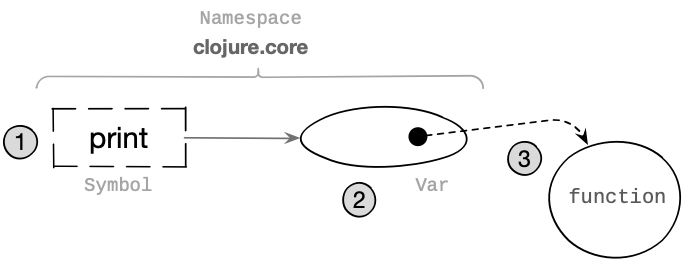

Let us look at a diagram illustrating how a function object is obtained from its name in our example program:

The evaluator performed 3 essential steps to obtain the invoked function’s subprogram:

-

It searched the namespace

clojure.coreto find the value assigned to the symbolprint. -

It obtained a

Varobject and passed it to the appropriate subprogram to read the current value of the reference. -

It found the function object pointed to by the reference variable, whose subprogram can be invoked.

Creating global variables is possible using the def special form:

1(def x 8) ; x points to the value 8

2(def y [1 2 3]) ; y points to the vector [1 2 3]

3(def write print) ; write points to the current value of print variable

4(declare later) ; creates a global variable without binding to a value

5

6(write x) ;=> 8

7(write y) ;=> [1 2 3]

8(write "Hello, Lisp!") ;=> Hello, Lisp!

9

10later

11;=> #object[clojure.lang.Var$Unbound 0x53245a5b "Unbound: #'user/later"]

(def x 8) ; x points to the value 8

(def y [1 2 3]) ; y points to the vector [1 2 3]

(def write print) ; write points to the current value of print variable

(declare later) ; creates a global variable without binding to a value

(write x) ;=> 8

(write y) ;=> [1 2 3]

(write "Hello, Lisp!") ;=> Hello, Lisp!

later

;=> #object[clojure.lang.Var$Unbound 0x53245a5b "Unbound: #'user/later"]

See also:

- “Bindings and namespaces”, chapter VI;

- “Global variables”, chapter VI.

Bindings

A binding is, in general terms, an association of an identifier with an identified object. Using this term helps us avoid misunderstandings related to the subtle but – from the programmer’s perspective – important differences in how objects are referred to by names.

In imperatively rooted languages we often use the concept of a “variable” and expect, by force of habit, that it will have some name. The term lets us point to a memory slot in which we will find a value. In Clojure this approach could be misleading, because we can create nameless variables (reference objects) as well as name values that are not variables at all.

In Clojure we encounter several kinds of bindings:

-

Global variables are bindings of:

- symbols to

Varobjects in namespaces, - symbols to Java classes in namespaces.

- symbols to

-

Lexical bindings are bindings of symbols to values within the binding vector of the

letspecial form. -

Parameter vectors are symbol binding forms with accepted arguments in function and macro definitions.

-

Structural bindings are abstract bindings of:

- symbols to values at indicated positions of sequential collections,

- symbols to values identified by keys of associative collections.

-

Reference type objects are bindings of objects to the current values they point to.

The last item requires explanation, because – as is easy to notice – it contains no mention of any symbol, and we have repeatedly stated that it is symbols that serve to identify other objects.

At this point it is worth recalling that in Clojure symbols do not

independently store references to values – this function is performed by

reference objects (e.g., of type Var in the case of global

variables). This follows from the adopted model of managing mutable state.

;; global variable

;; initial value pointed to by x is 1

(def x 1)

;=> #'user/x

;; parameter vector of a function definition

;; the first two arguments become parameters a and b

(fn [a b] (+ a b))

;=> #<Fn@5af25442 user/eval14406[fn]>

;; lexical binding

;; symbol a identifies the value 1

(let [a 1]

a)

;=> 1

;; positional decomposition in let

;; symbol a bound to value 1 by position

;; symbol b bound to value 2 by position

(let [[a b] '(1 2 8)]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; associative decomposition in let

;; symbol a bound to value 1 by key :a

;; symbol b bound to value 2 by key :b

(let [{a :a b :b} {:a 1 :b 2 :c 8}]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; associative decomposition in let (using :keys)

;; symbol a bound to value 1 by key :a

;; symbol b bound to value 2 by key :b

(let [{:keys [:a :b]} {:a 1 :b 2 :c 8}]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; binding a Var reference object to a value

(with-local-vars [x 5] x)

;=> #'Var: --unnamed-->

;; binding an Atom reference object to a value

(atom 5)

;=> #<Atom@a1cb453 5>

;; global variable

;; initial value pointed to by x is 1

(def x 1)

;=> #'user/x

;; parameter vector of a function definition

;; the first two arguments become parameters a and b

(fn [a b] (+ a b))

;=> #<Fn@5af25442 user/eval14406[fn]>

;; lexical binding

;; symbol a identifies the value 1

(let [a 1]

a)

;=> 1

;; positional decomposition in let

;; symbol a bound to value 1 by position

;; symbol b bound to value 2 by position

(let [[a b] '(1 2 8)]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; associative decomposition in let

;; symbol a bound to value 1 by key :a

;; symbol b bound to value 2 by key :b

(let [{a :a b :b} {:a 1 :b 2 :c 8}]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; associative decomposition in let (using :keys)

;; symbol a bound to value 1 by key :a

;; symbol b bound to value 2 by key :b

(let [{:keys [:a :b]} {:a 1 :b 2 :c 8}]

(+ a b))

;=> 3

;; binding a Var reference object to a value

(with-local-vars [x 5] x)

;=> #'Var: --unnamed-->

;; binding an Atom reference object to a value

(atom 5)

;=> #<Atom@a1cb453 5>

See also:

- “Bindings and namespaces”, chapter VI.

Collections

A collection is a data structure that allows storing a certain number of elements.

Lists

In Lisp the most commonly used data structure is the list, which – as we have had the chance to observe – serves both for the syntactic organization of program code (list S-expressions) and for storing ordered collections of elements for the purposes of application logic. It is worth thinking of a list as a way of arranging data, not merely a symbolic notation with parentheses.

There are several kinds of lists. The most commonly used in Lisp dialects are so-called linked lists, and more specifically singly linked lists. They are characterized by the ability to flexibly link elements together and to quickly add new ones to their beginnings. This is why they serve their role well as in-memory representations of Lisp program structures.

Lists in early Lisps

Historically speaking, each node of a list (in Lisp called a cons cell) has two slots: the first points to the value of the current element, and the second to the next element of the list (the next cons cell). In reality these are simply two pointers that can refer to arbitrary values.

Access to the first slot of each element is called car (from Contents of

the Address part of Register number), and to the second cdr (from Contents

of the Decrement part of Register number). The etymology of these peculiar

names goes back to the time when Lisp was implemented on the IBM 704 computer

(the 1950s). That machine had a special instruction that divided a 36-bit

machine word into 4 parts – car and cdr are the abbreviated labels of the

first two, and they found their way into Lisp because the author used them to

divide the contents of the internal structure representing a list cell. In

jargon, the first slot of a cons cell is therefore referred to as CAR, and the

second as CDR.

There is nothing preventing a list from containing another list within it:

In code we can express the above structure as:

(one two (1 2))

(one two (1 2))

that is:

1(one ; first element of the list

2 two ; second element of the list

3 ( ; third element of the list -- a nested list

4 1 ; first element of the nested list

5 2)) ; second element of the nested list

(one ; first element of the list

two ; second element of the list

( ; third element of the list -- a nested list

1 ; first element of the nested list

2)) ; second element of the nested list

And here is the notation using so-called full notation, which is not used in Clojure. Inside each pair of parentheses we find two slots separated by a dot:

(one . (two . ((1 . (2 . nil)) . nil)))

(one . (two . ((1 . (2 . nil)) . nil)))

The dots separate the CAR and CDR registers of the cells, and the nil

elements denote the ends of lists. If the second slot (CDR) is to point to the

next element of the list, in this notation that next element is placed after the

dot and enclosed in parentheses.

Let us remember, however, that the notation (one two (1 2)) is a valid

S-expression but not a form – unless we define a function named one and

associate the symbol two with some value. We can also use quoting to strip

the construct of its special meaning so that it expresses a constant form:

'(one two (1 2))

'(one two (1 2))

In the earliest editions of Lisp, lists were constructed using the cons

function (from construct). For example:

(cons 'one (cons 'two (cons (cons 1 (cons 2 nil)) nil)))

(cons 'one (cons 'two (cons (cons 1 (cons 2 nil)) nil)))

Which can also be presented as:

(cons 'one

(cons 'two

(cons (cons 1

(cons 2 nil))

nil)))

Such list construction may exercise the mind, but it does not serve productive

programming. At present some Lisp dialects have dropped support for full

notation, although the cons function is still used – mainly for

performing operations on existing lists rather than constructing them from

scratch.

Lists in Clojure

In Clojure, lists are represented by the host system’s object data type called

clojure.lang.PersistentList. Objects of this type can be found in the syntax

tree, where they reflect list S-expressions, as well as in application data

when the list function is used or a literal list is produced by

quoting its symbolically expressed form.

1(list 1 2 3) ; using the list function (arguments will be evaluated)

2(quote (1 2 3)) ; literal list (arguments will not be evaluated)

3'(1 2 3) ; literal list (arguments will not be evaluated)

(list 1 2 3) ; using the list function (arguments will be evaluated)

(quote (1 2 3)) ; literal list (arguments will not be evaluated)

'(1 2 3) ; literal list (arguments will not be evaluated)

Internally, PersistentList objects are doubly linked lists, although this

property is hidden from the programmer. Moreover, in Clojure a list (like most

data structures) is immutable – to introduce a change in its structure one

never modifies the object representing it but instead creates a new one that

differs from the previous one.

See also:

“Lists”, chapter IX.

Sequences and Cons objects

Apart from encapsulated lists, Clojure also provides objects of type Cons

(more precisely clojure.lang.Cons). They are the closest counterpart of

cons cells known from other Lisp dialects. More precisely, using cons we can

construct so-called sequences – abstract collections characterized by

a uniform access interface consisting of three basic operations:

- reading the value stored in the cell,

- reading the next cell linked to the current one,

- attaching a new cell to an existing one.

We can place references to values of arbitrary types in Cons objects and link

them into sequences using the cons function. It accepts two

arguments: a value and an object also equipped with a sequential interface

(these include, among others, lists, vectors, and maps). The returned

value will be a Cons cell whose next cell is the one provided as an argument.

If the provided existing object is nil, a single-element list will be

returned.

1(def the-first (cons 3 nil)) ; creates the list (3)

2(def the-second (cons 2 the-first)) ; creates cons(2)-->(3)

3(def the-last (cons 1 the-second)) ; creates cons(1)-->cons(2)-->(3)

4

5(first the-last) ; => 1 ; value in the last added cell

6(first (rest the-last)) ; => 2 ; value in the next cell

(def the-first (cons 3 nil)) ; creates the list (3)

(def the-second (cons 2 the-first)) ; creates cons(2)-->(3)

(def the-last (cons 1 the-second)) ; creates cons(1)-->cons(2)-->(3)

(first the-last) ; => 1 ; value in the last added cell

(first (rest the-last)) ; => 2 ; value in the next cell

Using Cons we can join not only individual values but also collections

(e.g., ordinary lists). We then have a compound structure that can be

expressed, for example, like this:

(cons (list 1 2 3)

(cons (list 4 5 6)

(cons 10

())))

; => ((1 2 3) (4 5 6) 10)

Such structures are sometimes used to quickly join already grouped values into larger sets that are flattened only when being read in order to obtain individual values.

(flatten

(cons '(1 2 3) (cons '(4 5 6) (cons 10 nil))))

; => (1 2 3 4 5 6 10)

See also:

“Cons cells”, chapter X.

Vectors

A vector is an ordered collection of values indexed using integers starting from 0 (the first element). In program code we use the vector literal to express vectors; we can also use several built-in functions.

Vectors in Clojure are represented by objects of type

clojure.lang.PersistentVector. They are characterized by very fast data

lookup and adding new elements to their ends. Vectors are also functions –

they accept one argument, an index number, whose element value will be

returned.

;; creating a vector (function)

(vector 1 2 3 4)

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; creating a vector from an S-expression (literal)

[1 2 3 4]

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; creating a vector from another collection

(vec (list 1 2 3 4))

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; searching a vector (element at index 0)

([1 2 3 4] 0)

;=> 1

;; creating a vector (function)

(vector 1 2 3 4)

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; creating a vector from an S-expression (literal)

[1 2 3 4]

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; creating a vector from another collection

(vec (list 1 2 3 4))

;=> [1 2 3 4]

;; searching a vector (element at index 0)

([1 2 3 4] 0)

;=> 1

See also:

- “Vectors”, chapter IX.

Maps

A map is an associative collection that stores mappings of keys to values. Keys and values may be data of any type, but the same key must be unique within a given map. Searching maps for a value identified by a key is very fast, as is adding new elements.

In Clojure, maps are represented by the following data types:

clojure.lang.PersistentHashMap(a map based on hash tables),clojure.lang.PersistentArrayMap(a map based on plain arrays),clojure.lang.PersistentTreeMap(a sorted map).

In program code we express maps using the map literal in the form of curly

braces containing pairs of expressions. We can also use the hash-map function